News

Field of Screens: eSports at NYIT

October 18, 2018

Top Photo: Members of NYIT’s eSports team, the CyBears, gather in the men’s locker room. Counterclockwise, left to right: Alexander Gusmano, Valiant Abello, Elieser Duran, Ryan Harran, Daniel Singh, and Kenneth Ng.

In their final set, before 20,000 breathless fans, the Spitfires attack with a combo of DPS frenzy, solid tank play, and teamwork on King’s Row (naturally, with a few well-placed ults). The crowd roars, and the Spitfires seal their place as champions.

If the preceding sentence made little sense, you’re not alone. But to the Barclays Center sellout crowd at the Overwatch League (OWL) Grand Finals on July 28, 2018, it was like hearing a baseball announcer say: “The Yanks clinched another World Series win with great fielding and clutch hitting in the ninth.”

Welcome to eSports, a skyrocketing industry and a new frontier on the collegiate athletics scene, where NYIT is poised to become a major player. In addition to its first-ever eSports team (the CyBears), the university has launched a Center for eSports Medicine to understand the injuries and physical fitness of cyber-athletes, a customized bachelor’s degree program tailored for students interested in emerging video game careers, and a new on-campus arena for competitive online gaming.

The 2018 Overwatch Grand Finals at Barclays Center in New York City.

ESports has experienced a tremendous rise in popularity, with professional leagues and teams sprouting up in cities worldwide. In 2015, ESPN The Magazine reported that the 2014 League of Legends championship attracted 27 million viewers, exceeding those of the NBA Finals (15.5 million), World Series (13.8 million), and the Stanley Cup finals (5 million). This year, eSports viewership is expected to reach 380 million (according to market intelligence firm Newzoo), and by 2020, this segment of the video game industry is expected to generate $1.4 billion in advertising, sponsorships, tickets, merchandising, and media rights. In many countries, eSports athletes are worshiped like rock stars and well-compensated. At the Overwatch Grand Finals, the London Spitfire and the Philadelphia Fusion competed for a $1.4 million prize pool.

“The world of eSports is such a phenomenon,” says Dan Vélez, director of athletics and recreation. “It’s become more legitimized now that major TV networks like ABC and ESPN are televising matches.” Many eSports fans also watch through Twitch, an online streaming platform with 15 million active daily users, which was sold to Amazon in 2014 for $970 million. John Rendemonti and Seth Mattox, co-founders of OPSEAT, which manufactures gaming GamingChairs, desks, and more (and is working with NYIT to research eSports player fitness), credit much of eSports’ popularity to platforms like Twitch as well as increased access to online games.

“It’s easier than ever to get into eSports,” says Rendemonti. “All you need is an internet connection capable of connecting at a speed to be able to compete. Just like chess, now everyone can play Fortnite.”

Higher education has also taken notice: More than 50 collegiate eSports teams have launched in the United States, according to the National Association of Collegiate Esports. In 2012, Blizzard Entertainment, publisher of three of the biggest eSports titles—Overwatch, Starcraft 2, and Hearthstone—founded an organization called Tespa to operate collegiate eSports leagues. They began reaching out to college online gaming clubs to include them in tournaments that would be broadcast worldwide. One group happened to be located in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Ready Player CyBear

Elieser Duran, a graphic designer, created the CyBears’ logo. The teeth resemble electrical resistors.

“We’d had some conversations internally within the athletics department about eSports,” recalls Vélez. “We were starting to see the traction of eSports across the country as it became more competitive and more popular.” At the same time, a group of NYIT students in the Game Club at the Long Island (Old Westbury, N.Y.) campus decided they wanted to focus more on online gaming. “Many of us were already bringing our laptops to Salten Hall to play during off-hours,” says Elieser Duran (B.F.A. ’17), one of the group’s founders. “So there was already a gaming culture at NYIT. After a year, we said, ‘Why don’t we start a team?’”

They approached former Athletic Director Duane Bailey and discovered he was already looking into an NYIT eSports team. In January 2017, the CyBears officially launched with eight players (“a ragtag group of whoever we could find,” notes Duran) and, through Tespa, began competing against other colleges.

“I do consider eSports a sport because there is a lot of mental energy required,” says Vélez, who is working with Twitch and PC gaming manufacturer Alienware (which is supplying the CyBears’ gaming rigs) on co-branding opportunities. “You have to learn to adapt to situations and possess a specialized skill set. The eye-hand coordination of an eSports athlete is through the roof.”

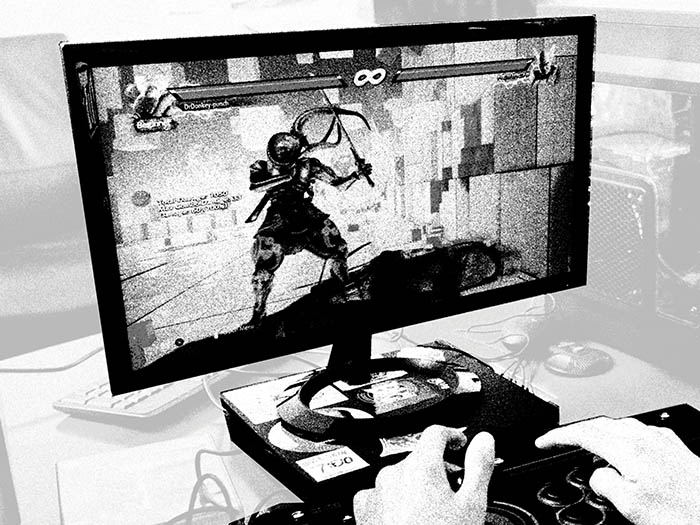

CyBear Valiant Abello, a fighting game player, plays Tekken 7. The CyBears compete in the East Coast Conference for League of Legends and also play games such as Hearthstone and Overwatch.

Today, the team includes more than 30 players from NYIT’s Long Island and New York City campuses, with its main games being Overwatch, Hearthstone, and League of Legends. This fall, the CyBears are competing in the East Coast Conference’s (ECC) inaugural eSports season against other colleges that include Mercy College.

Like their traditional sports brethren, the CyBears share a camaraderie on and off the field of play. “Everything is better with friends,” says computer science major Alexander Gusmano. Being a CyBear, he adds, “fulfills a social interaction I was looking for” at NYIT. As a transfer student new to NYIT, architecture student Ezekiel Cambara appreciated “being able to jump right in and be included in a group doing what we love.”

Watch the CyBears on News 12

Like traditional student-athletes, the CyBears not only compete against other colleges but also work to improve by scrimmaging against each other. Duran volunteers as the CyBears coordinator (he also manages the team’s Twitter: @NYIT_eSports), and like any good coach, he runs team tryouts and reviews gameplay footage on Twitch and YouTube to study other teams and look for weaknesses. The overall commitment to their game makes eSports athletes similar to their traditional counterparts where focus, discipline, time management, and dedication are paramount.

To welcome the CyBears to their ECC eSports debut, NYIT is building a new facility for them to practice and compete on the Long Island campus. The Wisser Arena will sport 12 fully loaded PC gaming stations in a 300-square-foot space, as well as several large TV screens for spectators to watch the action and a setup to broadcast games remotely. “We wanted a gathering space where people can watch eSports events,” says Greg Loeven (B.T. ’07), project manager of the Wisser Arena. “Here, we can host our own tournaments and play championship matches on our own stage. ESports is going to be big at NYIT, and we’re happy to be on the ground floor of it.”

Members of the CyBears, from left to right: Daniel Singh, Ryan Harran, Kenneth Ng, Alexander Gusmano, Elieser Duran, and Valiant Abello.

Extra Life Granted

Cyberathletes often play several hours a day using more than 400 body movements per minute with a mouse or keyboard. Although they are less likely to twist an ankle or pull a hamstring than traditional student-athletes, they are still susceptible to injuries. Eye, wrist, and back strain, as well as carpal tunnel syndrome, are among the more common ailments suffered by online gamers.

To better understand and treat these medical conditions, NYIT launched the Center for eSports Medicine. One of the first institutes of its kind, researchers will investigate how gamers can minimize ailments and maintain healthy lifestyles. “We had the quick realization that what eSports players are doing will give them injuries,” says Jerry Balentine, D.O., dean of NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) and vice president for health sciences and medical affairs. “Because most are young, they won’t realize many of the injuries that may come to pass until a later age. We want to help them stay healthy.”

The Center for eSports Medicine’s integrated eHealth team includes primary care and osteopathic manipulative medicine physicians as well as occupational and physical therapists. ESports athletes and other gamers can receive posture assessments to reduce neck, back, and wrist pain; proper body alignment to reduce eye strain; and individualized fitness programs using body composition and nutritional plans.

NYITCOM Assistant Professor Hallie Zwibel (D.O. ’11), who serves as the team physician for all NYIT athletic teams and is director of the Center for Sports Medicine, notes that working with the CyBears is an opportunity for NYIT to take a leading role in an under-researched area. “There is nothing in the field in terms of the healthcare needs, problems, and best practices as it relates to what eSports players need,” he says.

“We have an opportunity and responsibility to do this work,” adds NYITCOM Assistant Professor Joanne Donoghue, Ph.D., who was also trained in traditional sports medicine and co-wrote a paper with Balentine for the American College of Sports Medicine that examines the integration of eSports and health professions.

“It’s really exciting that we’re at the forefront of this unknown area of medicine.” There is also research to support that eSports provides some cognitive benefits. In 2014, the American Psychological Association published a review that demonstrated how online gaming (yes, even violent shooting games) may “strengthen a range of cognitive skills such as spatial navigation, reasoning, memory, and perception.” Other studies concluded that video games helped promote problem-solving skills, boosted positive feelings among young people, and helped them recover from failure.

Right now, however, health professionals have little understanding about the nutritional requirements and fitness needs of the typical eSports athlete—and that means there’s an opportunity to get ahead of the pack. At the Center for eSports Medicine, Zwibel and his colleagues examine how eSports athletes can improve their game beyond simply gaming. “ESports players rely on gameplay practice as their only form of training, which is the opposite of traditional athletes,” says Zwibel. “For example, soccer players don’t just practice on the field, they also lift weights and perform other exercises. … One of the things we’re looking at is overtraining. For example, at what point does [playing games] become counterproductive, with many eSports athletes gaming up to eight hours a day?”

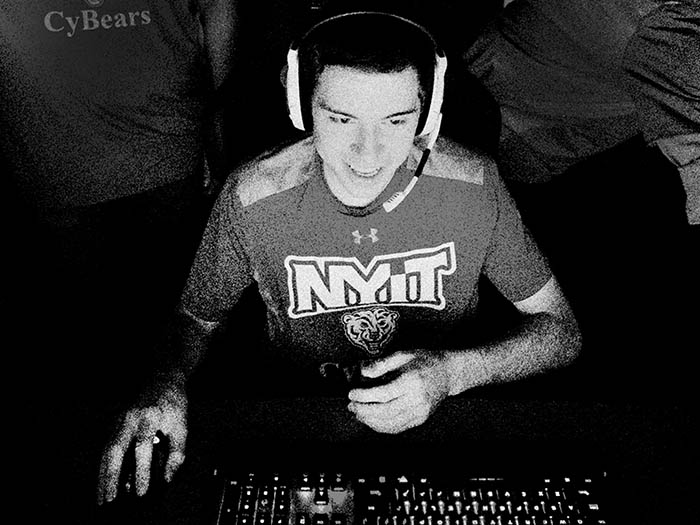

CyBear Ryan Harran at team practice.

A collaboration with the University of California to study melatonin levels in collegiate eSports players may lend new insights into players’ productivity. “Melatonin is an important biomarker that affects sleep patterns and can be disrupted by too much exposure to blue lights on computer screens,” says Donoghue. “We found abnormal patterns in our eSports athletes.”

NYITCOM researchers have also monitored the CyBears’ physical activities by providing Fitbits. One of the things Donoghue discovered was that the CyBears were only taking about 4,000 steps per day—half the recommended amount. With data like this, Donoghue and the team can better help the players hone their physical activity levels, even if they think their Overwatch fighting skills are at peak performance.

“They know what to do to be good at the game,” she says. “I know what they need to do to be healthy.”

Well Seated

So, what makes a

good gaming chair?

According to OPSEAT co-founders Rendemonti and Mattox, it’s ergonomic design, customization for a variety of body sizes, and an affordable price. (OPSEAT chairs are priced between $200 to $250.)

One unique aspect of the Center for Sports Medicine’s research is its partnership with gaming chair manufacturers OPSEAT and Vertagear. “NYIT is the only one that has approached us to discuss the ergonomics of eSports,” says OPSEAT co-founder Rendemonti. “To have a medical institution back it up, it doesn’t get much better than that.”

“With gaming chairs, we’re looking at an eSport athlete’s posture,” says Donoghue. “We want to study the impact on those postural movements using NYIT’s broad expertise in osteopathic medicine, physical therapy, occupational therapy, physician assistant studies, and other healthcare specialties.”

When CyBear and biology student Daniel Singh participated in one chair study, NYITCOM researchers assessed his range of body motion and neck movements while he sat in the chair and played games. Ultimately, NYIT plans to supply OPSEAT and Vertagear with research that will help inform future designs and provide enhanced ergonomic support.

In the meantime, both companies are co-sponsors of the CyBears and are donating equipment for the team’s new arena.

Gaming a Career

Athletes in every sport face a limited career life span, but for gamers, retirement typically hits by the mid-20s. Even top-earning players, such as NYIT’s own Dominique “SonicFox” McLean, who is listed in Guinness World Records 2018 Gamer’s Edition as the highest-earning fighting video games player, need to plan for a “second” career. But that doesn’t mean they need to look outside their industry.

Revenues from worldwide video game sales—which includes eSports titles; Nintendo, Xbox, PlayStation, and PC games; and mobile apps—continue to score big for investors. Newzoo’s Global Games Market Report estimates that video game fans will spend up to $138 billion on games in 2018 alone. (By comparison, the global box office revenue for 2017 totaled $40.6 billion.)

Is DPS Frenzy Like Pac-Man Fever? An Esports Glossary

Competitive eSports gamers speak their own jargon that may seem like gibberish to the unfamiliar. Here’s a quick primer on common gamer slang:

BOSS: An AI-controlled opponent that is more difficult to fight than other enemies.

COMBO: A series of attack moves in rapid succession.

DPS: “Damage per second.” A common video game statistic that represents the offensive power of a character or weapon.

DLC: “Downloadable content,” which refers to additional game content (maps, characters, weapons, etc.) that can be downloaded for a game.

NERF: To diminish the power of a character or weapon. Designers of eSports titles often “nerf” their games to tweak balance and promote fair gameplay.

NPC: “Non-player character,” which is controlled by the game’s AI (as opposed to human player characters or “PCs”).

OP: “Overpowered,” or game effects that are too powerful. OP elements in a game are often “nerfed” by the game’s designers.

PVP: “Player vs. player,” or gameplay in which two human players compete against each other (as opposed to “PvE,” or “player vs. environment,” in which a player competes against the game’s AI-controlled NPCs).

TANK: A type of character adept at absorbing damage from the enemy to protect teammates.

ULT: A character’s “ultimate” move that unleashes an overwhelming offensive or defensive ability that greatly benefits their team.

To help students prepare for careers in the booming eSports industry, NYIT School of Interdisciplinary Studies and Education offers interdisciplinary studies majors a personalized academic learning map called “Game Design and Visualization” to guide them. Students can choose from concentrations including: digital arts, computer science, and management.

“You can begin the interdisciplinary studies bachelor’s degree and start with those three concentrations but later pick the industry sectors where you would like to work,” says Christian Pongratz, M.Arch., interim dean of NYIT School of Interdisciplinary Studies and Education. Other concentrations planned include health professions, communication arts, and technical writing. “There are a wide range of skills that can be used in eSports development,” adds Pongratz. He also plans to integrate augmented, virtual, and mixed reality technology into the curriculum. “This is an emerging market, and we want creative NYIT students to really spearhead game design in this part of the industry,” says Pongratz.

CyBear and architecture student Valiant Abello shows off a new controller in the NYIT fitness center.

Developing and marketing games are just some of the ways gaming enthusiasts can turn their passion into their career. “Gaming nutritionist,” “eSports agent,” and even “Overwatch Grand Finals halftime performer” are on the table as potential options. With a little ingenuity, networking, and the right skill sets, anyone can find a niche in this evolving field.

Perhaps the biggest question, however, is what do parents think about all this? After all, the Gen Xers who were grounded for playing Super Mario Bros. on the original Nintendo while they should have been studying for SATs may not be convinced that eSports as a career “is a thing.”

“At first they were a little ‘eh,’” remarked CyBear Cambara in a Facebook live conversation with News 12 Long Island in August. “But now they see how big it’s gotten—we’re getting an arena, we’re going to these events—and they’ve grown accustomed to it.”

Added teammate Singh: “I’ve had no complaints.”

Is DPS Frenzy Like Pac-Man Fever? An Esports Glossary

Competitive eSports gamers speak their own jargon that may seem like gibberish to the unfamiliar. Here’s a quick primer on common gamer slang:

BOSS: An AI-controlled opponent that is more difficult to fight than other enemies.

COMBO: A series of attack moves in rapid succession.

DPS: “Damage per second.” A common video game statistic that represents the offensive power of a character or weapon.

DLC: “Downloadable content,” which refers to additional game content (maps, characters, weapons, etc.) that can be downloaded for a game.

NERF: To diminish the power of a character or weapon. Designers of eSports titles often “nerf” their games to tweak balance and promote fair gameplay.

NPC: “Non-player character,” which is controlled by the game’s AI (as opposed to human player characters or “PCs”).

OP: “Overpowered,” or game effects that are too powerful. OP elements in a game are often “nerfed” by the game’s designers.

PVP: “Player vs. player,” or gameplay in which two human players compete against each other (as opposed to “PvE,” or “player vs. environment,” in which a player competes against the game’s AI-controlled NPCs).

TANK: A type of character adept at absorbing damage from the enemy to protect teammates.

ULT: A character’s “ultimate” move that unleashes an overwhelming offensive or defensive ability that greatly benefits their team.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of NYIT Magazine