News

Dangerous Books. Who Decides? And Should They?

October 24, 2023

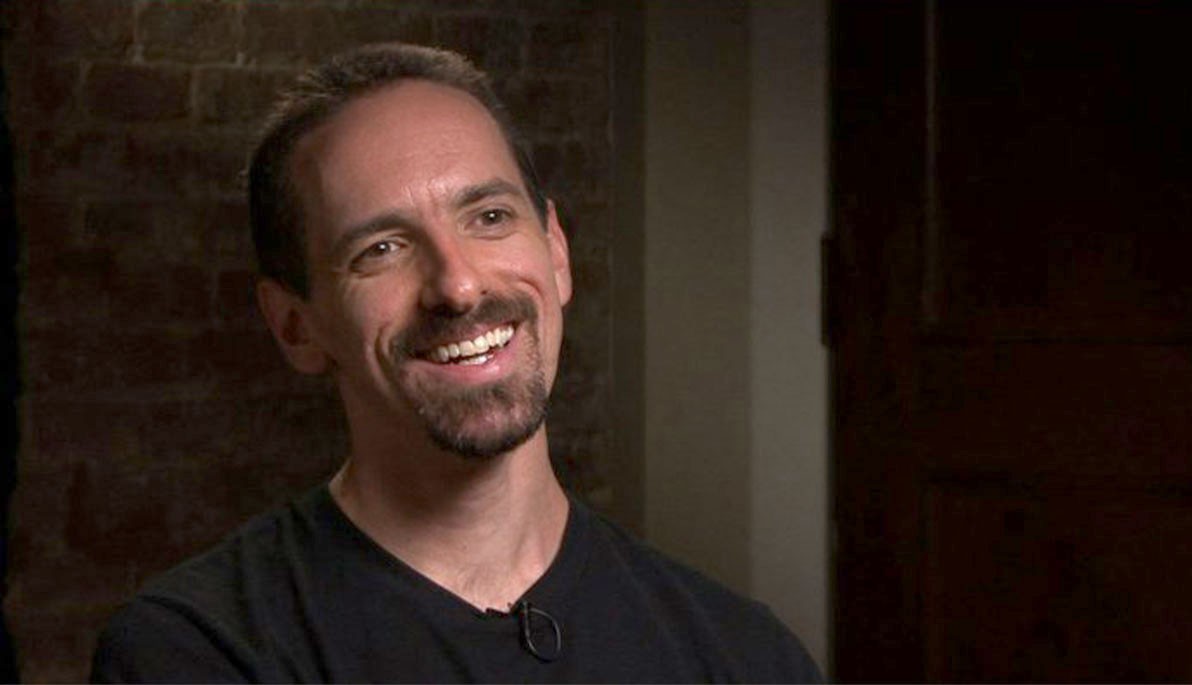

Professor of Humanities Michael Schiavi, Ph.D., tackles banned books in his course Dangerous Books, a class he has taught several times since 2005. “When I first taught the course, we were in a very different political climate,” he says. “Book banning and book challenges existed then, but they weren’t nearly as common as they are today. At the time, I wanted to engage students in a discussion about censorship of books that they would have the chance to judge for themselves.”

Schiavi spoke to New York Tech News about the class, which will be offered in the spring 2024 semester, and the dangers of deciding what people can and can’t read.

Can you tell us about the class? What can students expect?

I used to begin the course with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic novel The Scarlet Letter (1850), perhaps the least scandalous, most restrained book in American literature. Yet banners had wanted to yank it off shelves for being supposedly filled with “prostitution” and “four-letter words.” After students had read the novel, I asked them how they responded to those charges. It was great to see their eyes light up as they answered, “Anyone who would say those things about the book must have never read it.” Exactly. There is zero mention of prostitution, much less the use of four-letter words, in Hawthorne’s mid-19th century book. But people who try to block youth from reading very often don’t take the time to read what they’re banning.

What will the curriculum be about? What will students learn?

We’ll be reading a range of books that are commonly banned. Students will learn why those books have been banned, for which populations, and in which political circumstances. They’ll be asked to assess the bans: to think about what assumptions have caused them and what effects such books might have on young readers if they are permitted to discover them.

What kinds of projects will the students be required to undertake?

In addition to our shared course readings, students will work on a project that I call Banned at the Strand. The Strand is Manhattan’s largest used bookstore. It actively promotes a list of commonly banned books. Students will choose one of these books and write up a report/presentation for the class on the book’s history of being banned, as well as the students’ own assessments of their books and the bans.

How did you come up with the name for the class?

I came up with that title because, as a lifelong reader, it’s always seemed outrageous to me that anyone could consider books “dangerous.” Books are portals to other worlds. They take us to places we never dreamed of and introduce us to people and ways of life that we might never have the chance to see in person. Yet to banners, books plant “dangerous” ideas in students’ minds. Overwhelmingly, those ideas are about validation of LGBTQ+ existence, acknowledgment of sexuality and sexism, challenges to racism, and questioning the political or economic status quo. Banning books doesn’t keep students away from such topics. It only makes them more curious about them. And that’s a good thing. For example, when I was growing up, there was zero representation of LGBTQ+ characters in children’s literature. It would have meant the world to me as a gay kid to see myself represented in books. Reading about a gay character would not have “turned” me gay, which I already and always was. It simply would have made me feel better about myself. Who wouldn’t want that for a child?

What do you hope students will take away?

More than anything, I want students to consider what it means when individuals—whether politicians, teachers, religious leaders, parents—decide that a book is “dangerous” and should be hidden from public view. How do students feel when someone has decided that they're not “mature” enough for a particular book, or that a particular subject shouldn’t be examined?

The American Library Association reported 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022. What are the dangers of removing books off library shelves? Whenever anyone takes it upon themselves to decide who has the right to read what, democracy itself is threatened. Our ability to make choices about our leaders and the laws that govern our country depends on our access to information. Banners are very aware of this. They hope that if they keep certain titles out of sight, they won’t have to worry about ideas that threaten their control. The irony is, as any parent knows, the surest way to make a child want to learn about something is by telling them it’s forbidden. Also, in this digital age, the notion that yanking a book off a shelf will keep it permanently hidden is ridiculous.

Which banned books do you recommend that people read? Why?

Oh, such a range! You could start with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, which banners have feared for its portrayal of teen sexuality and suicide. Moving closer to our times, such classics as Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird have inspired bans for their honest portrayal of racism—a topic that many banners want to erase from the teaching of American history, as if to suggest that it’s never existed. What better way to continue inequality than by teaching young people that it’s all a fantasy? With the recent overturning of abortion rights, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, about a totalitarian society in which women are forced into sexual slavery in order to ensure population growth, is entirely appropriate. Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue provide both fictional and autobiographical looks at young people who are not heterosexual or cisgender: How do they cope with growing up in a society that may reject them based on the very core of their identity?

This interview has been edited.

Registration for the spring 2024 semester runs from November 6 through January 21, 2024.

_Thumb.jpg)