Realistic 3-D Colon Model Shifts Paradigm for Drug Development

Several years before joining New York Tech, Steven Zanganeh, Ph.D., faced a frustrating reality of his research in developing new cancer treatments: 90 percent of novel clinical drugs that perform well in lab studies fail to pass muster in human clinical trials because of inefficacy, toxicity, and other reasons.

Zanganeh vowed to improve the lab systems that he says contribute to these failures, particularly the non-human models that are typically used to study drug responses.

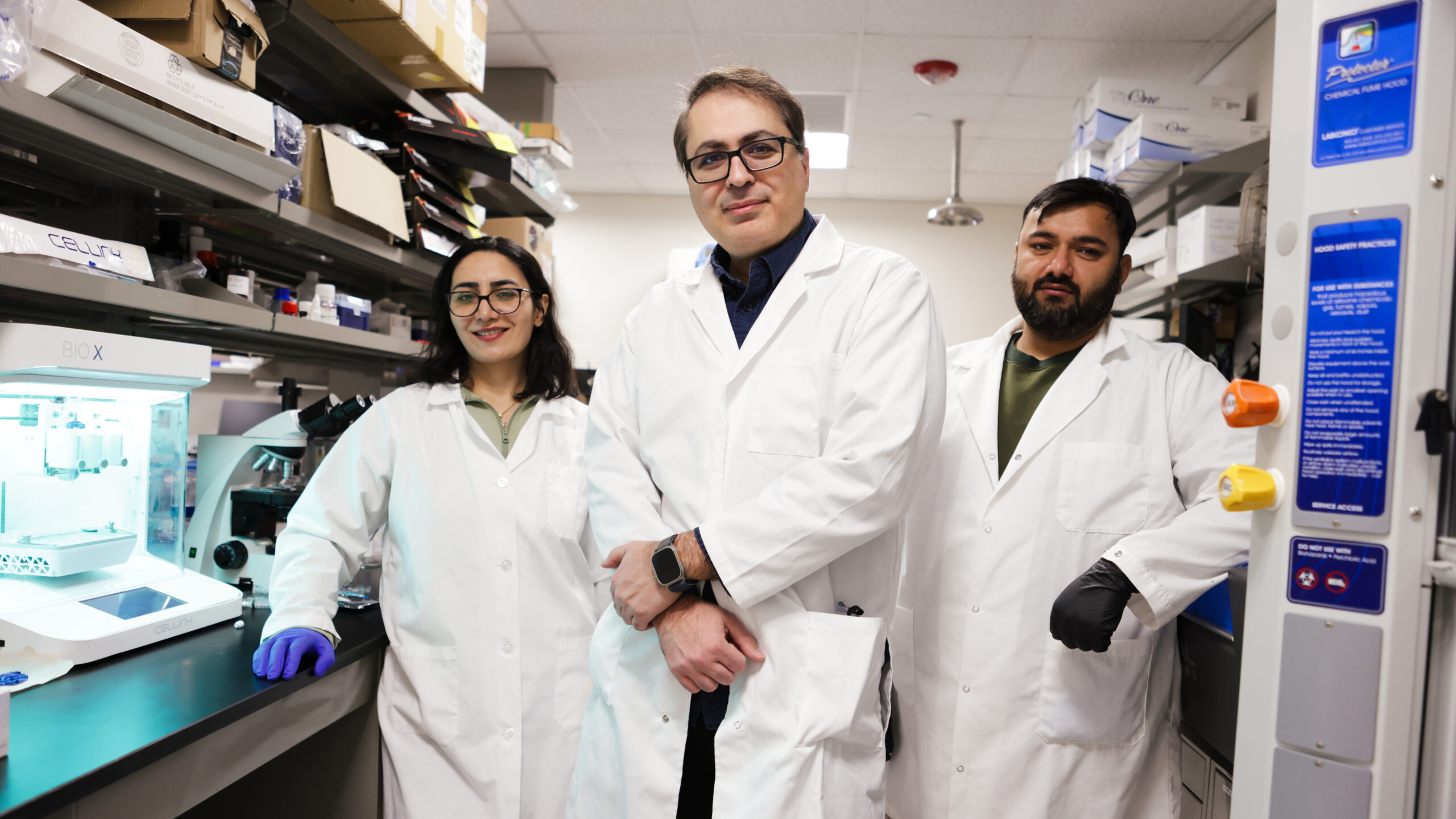

“I became convinced that we could take advantage of tissue engineering to create 3-D engineered human tissue models that mimic native tissue and respond to drugs in a clinically relevant way,” says Zanganeh, who dove into this work shortly after starting at New York Tech in winter of 2024 as an assistant professor in the bioengineering program within the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Zanganeh set his sights on engineering functional 3-D human tissue models to study therapeutic response in metastatic cancer. He began with the colon because colorectal cancer is a major clinical challenge and because his prior work focused on colorectal cancer metastasis to the liver. He also recognized that 3-D bioprinting could enable a realistic, scaled-down gut architecture.

Traditionally, colon cells, like most lab-grown cells, are cultured in 2-D monolayers on the bottom of petri dishes or flasks. Although the method is easy and scalable, it doesn’t replicate the morphology, interactions between cells, microenvironment, and other properties of actual tissue. Zanganeh says that researchers have been trying to develop 3-D cultures that overcome these limitations for the last decade, but the results, which include organ-on-a chip and spheroid models, do not look and act like colon tissue.

In a recent multi-institutional study in the journal Advanced Science, Zanganeh and his colleagues present the results of their quest to improve the world of 3-D cell culture. Their model, called in vivo mimicking human-colon model (3D-IVM-HC), is based on bioprinting a soft gel that serves as a scaffold for both colon cells and their supporting cells known as fibroblasts. Tests of the model revealed that it captures both the intricate morphology of colon tissue and complex functions such as nutrient absorption.

To test 3D-IVM-HC’s potential role in cancer drug development, the research team planted a lab-grown colorectal tumor in the model and then treated it with 5-fluorouracil, a common chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. They found that higher doses of chemo were needed to have cytotoxic effects on this tumor than for tumors grown in 2-D and simple 3-D models, suggesting that 3D-IVM-HC may be more informative than those other systems about effective dosing for patients.

Although Zanganeh notes that the research is still in early stages, “this is the future of drug development.” Further down the road, the model may reduce the reliance on animal studies in preclinical research and open new avenues for drug development for other diseases.

Building a Better Model

About 10 years ago, Zanganeh, then a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine studying the role of iron in cancer growth, began hearing about the development of organ-on-a-chip systems. In this model, different types of cells can be grown together on small chips outfitted with channels and other features to control the cellular environment.

The concept made an impression on Zanganeh, as it did for Rahim Esfandyar-Pour, Ph.D., his good friend who was also a Stanford postdoc at the time. They continued discussing how to push 3-D culture systems after Zanganeh moved to the East Coast and joined Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center as a senior scientist. In parallel, Esfandyar-Pour established a program at the University of California, Irvine, centered on advanced bioprinting and wearable biosensor technologies, and began adapting organ-on-a-chip approaches for colorectal cancer drug screening.

Seeing the complementary strengths, Zanganeh proposed a collaboration to merge Esfandyar-Pour’s bioprinting capabilities with Zanganeh’s cancer therapy and translational modeling expertise to develop an improved 3-D human colon tissue platform.

Esfandyar-Pour and his lab had the equipment at the ready, and with Zanganeh’s input, began building. The bicoastal team consulted existing human colon CT (computed tomography) scans to design a pattern for bioprinting that mimicked the long tubular shape of the intestine and its detailed architecture on a small scale—only a few centimeters in each direction. The “ink” for printing was a combination of hydrogels that mimic space around cells, or extracellular matrix, in the body, which the team notes is an important component missing from other 3-D models. To help recreate the extracellular matrix, the team embedded the gel with fibroblasts, a cell type that sends critical signals to colon and other cell types to guide their growth and function. Finally, they seeded colon cells on the hydrogel inside the tubular structure.

As the colon cells grew in 3D-IVM-HC over the next two weeks, the team could tell that they looked like actual colon tissue under the microscope, forming deep, well-like structures called crypts that are hallmarks of intestinal tissue.

But to deem the model functional, the team had a list of properties they wanted the colon cells to exhibit based on computational modeling they carried out of colon activity in vivo (in the body). These included absorbing water and nutrients and adhering to each other to form a barrier (shown experimentally by testing electrical resistance of the culture). One by one, the properties of colon cells in the 3D-IVM-HC model matched the computer models. “We knew this was a human function-mimicking model like nothing else available right now,” Zanganeh says.

Part of the Cancer Drug Development Pipeline

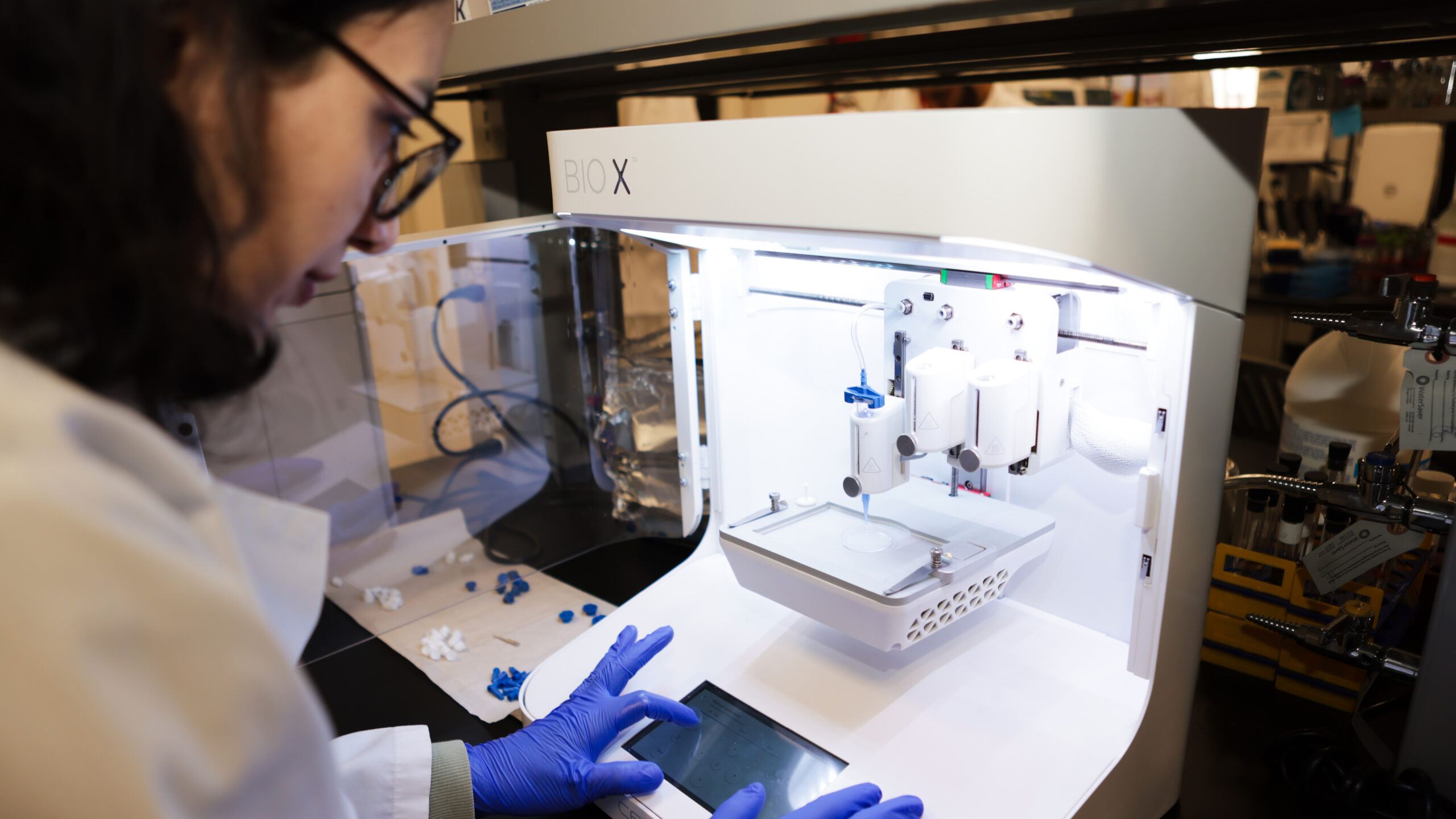

Zanganeh recently acquired his own printer and other equipment to produce 3D-IVM-HC. His lab, made up of graduate and undergraduate engineering and bioengineering students and a medical student, is using them to further improve the model. One of the main priorities is to integrate immune cells and blood vessels into the model, making it even more like in vivo colon tissue.

“My dream is to use the model to test cancer drugs—not traditional chemotherapeutic drugs, but immunotherapies,” Zanganeh says. Immunotherapies such as Keytruda emerged about 15 years ago and are now used as treatment for a range of cancer types. Because they work by modulating immune cells to attack tumors, testing the activity of new immunotherapeutic compounds in cell culture requires that the cell cultures contain immune cells.

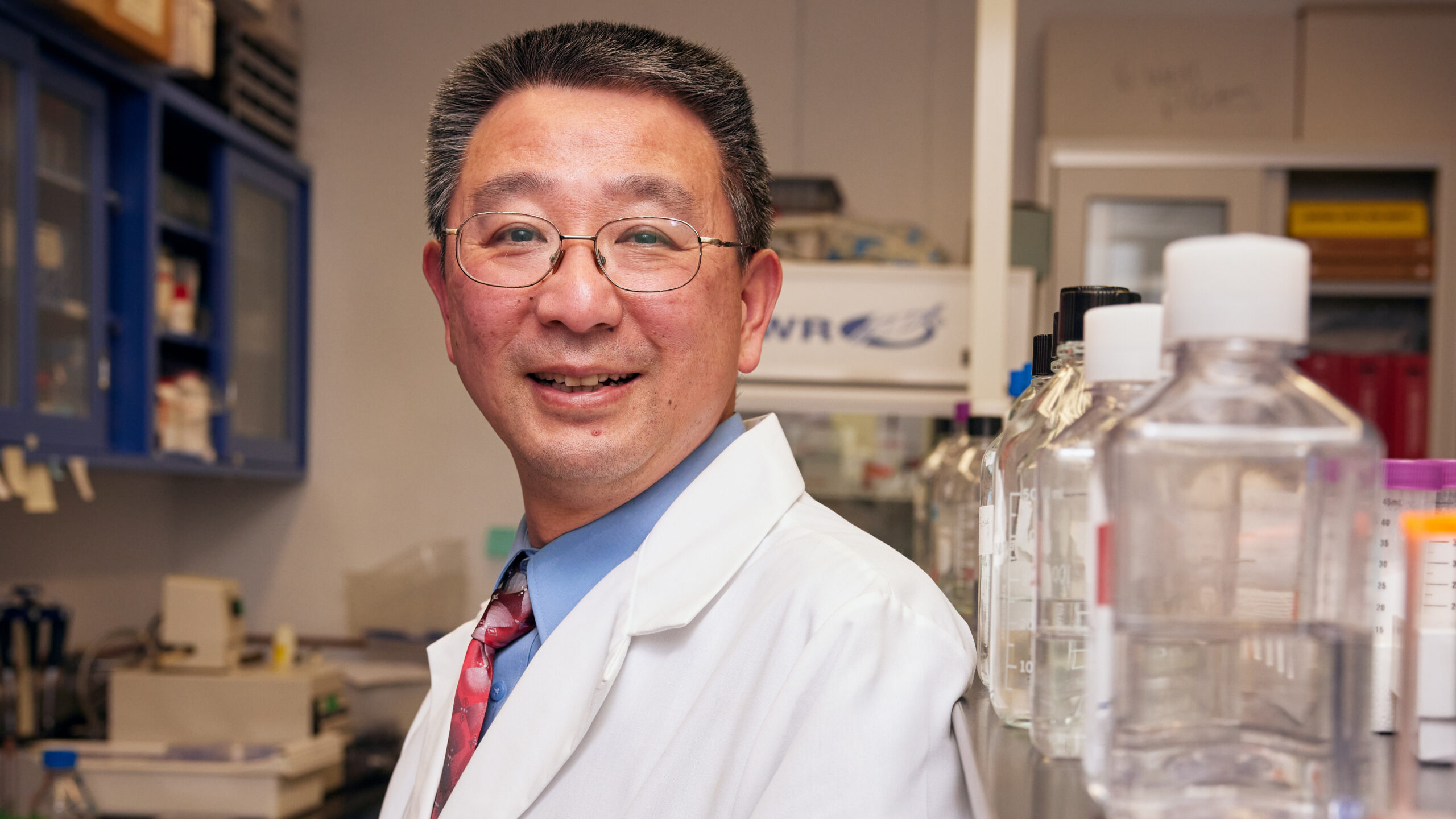

The model could also become part of the drug development pipeline for Dong Zhang, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical sciences at New York Tech and director of the Center for Cancer Research, who studies new cancer therapies targeting DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways.

One of the advantages of 3-D models like Zanganeh’s is that they are less stressful for cells, Zhang says. “When you grow tumors in a petri dish for a long time, they may adapt to that particular environment and may not look like a real tumor,” explains Zhang, who developed cancer drugs at a pharmaceutical company before joining New York Tech.

A longer-term goal is to grow cells from tumors from patients in the 3D-IVM-HC model to study a wide range of tumor biology and drug response. So far, Zanganeh and his colleagues have grown only two types of lab-based colon cell lines in the new model; Zanganeh sees no reason that cells from patients wouldn’t grow well in 3D-IVM-HC. Zhang may help in this area, as he has been teaming up with Catholic Health Cancer Institutes on Long Island to train New York Tech medical students and says they could now collaborate to study samples from their patients in the 3-D model.

Endless Applications for Tissue Engineering and Medicine

In addition to the limitations of 2-D cell culture, Zanganeh says that an important reason so many novel clinical drugs fail is that they are studied in animal (often mouse) models of disease after studies in 2-D cell culture—and neither lab system really reflects the disease in people. There are just too many biological differences between mice and humans, not to mention the cost, time, and ethical concerns with animal experiments, Zanganeh notes. For these reasons, he adds, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced in April 2025 that it would phase out requirements for animal drug testing.

3-D models would be a better lab system, according to both Zanganeh and Zhang. Many pre-clinical studies of gene expression changes, immune response, and toxicity associated with a new drug are done in mouse models but could instead be conducted in a fully functional 3-D model, Zanganeh says.

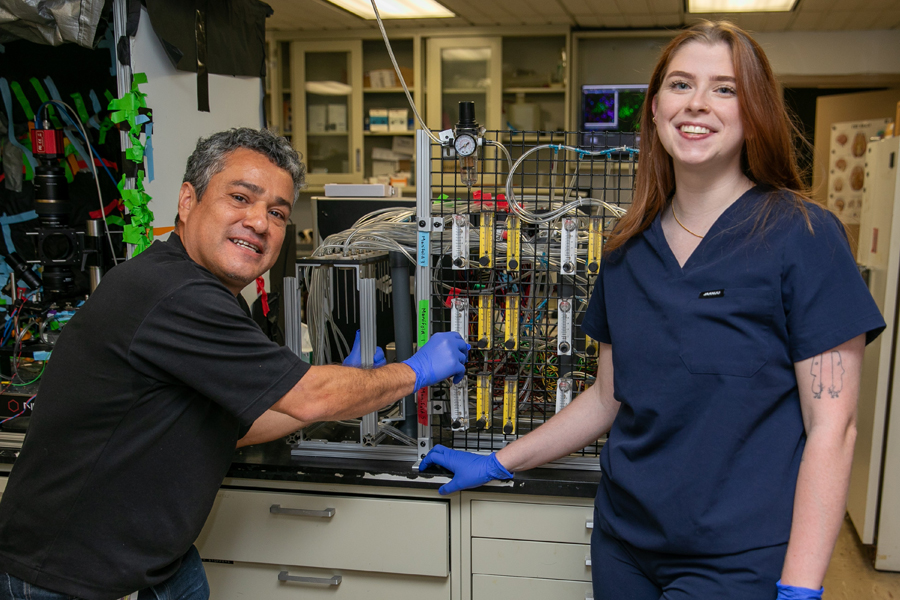

The approach that Zanganeh and his colleagues took for 3D-IVM-HC could probably be adapted for any tissue type from the heart to the eye. Aydin Farajidavar, Ph.D., director of Integrated Medical Systems (IMS) Laboratory and professor of electrical and computer engineering at New York Tech, is interested in building upon it to study gastrointestinal tissue.

One area of Farajidavar’s research explores stomach conditions such as gastroparesis, which slows stomach emptying and causes pain and indigestion. His lab has done work to understand the role of electrical simulation both to diagnose and treat these conditions. However, Farajidavar notes that the research is currently limited to computer models and animal models.

“There have not been any 3-D models of the stomach,” Farajidavar says. In fact, he adds that his group could even study electrical simulation using 3D-IVM-HC, although their experiments would require any 3-D model to contain nerve cells, which may be a tricky addition.

The ways that the 3-D colon model could be updated and improved, such as by integrating neurons, are seemingly endless. That is why Zanganeh plans to stay focused on this aspect of the work, even though the potential is enormous to venture into areas such as precision medicine (creating a personalized culture from a patient’s tumor cells to guide treatment decisions) or scaling up the cultures to grow organs for transplant patients.

“This is a very new paradigm in tissue engineering and medicine,” Zanganeh says.

By Carina Storrs, Ph.D.

More News

Understanding the Human Machine

Biology student Justin Tin seeks to understand what’s running “under the hood” in the human body so he can someday help prevent patients from suffering physiological changes.

Study: VR Helps Children With Autism Participate in Exercise and Sports

A new study by researchers from the School of Health Professions and College of Osteopathic Medicine demonstrates how virtual reality (VR) can help children with autism spectrum disorder participate in exercise.

Driven by ‘Why’

Third-year medical student Kassandra Sturm leads the charge on a new study helping to uncover the neurological source affecting the sense of smell in autism spectrum disorder.

Technology Partnership Helps Children With Disfluencies

Former NBA star Michael Kidd-Gilchrist has partnered with the College of Engineering and Computing Sciences’ ETIC to develop a prototype of a technology platform that he hopes will help children who stutter.

Engineering a Cancer Treatment Game Changer

A groundbreaking project co-led by the College of Engineering and Computing Sciences’ Steven Zanganeh, Ph.D., provides the world’s first functional, drug-testable, 3-D-printed human colon model.

Gut Instincts: Solving Microscopic Mysteries

Research by NYITCOM Assistant Professor Vladimir Grubisic, M.D., Ph.D., aims to deliver findings that could pave the way for new treatments benefiting patients with gastrointestinal and neurological diseases.