News

Researchers Go Toe-to-Toe With Horse Evolution

January 24, 2018

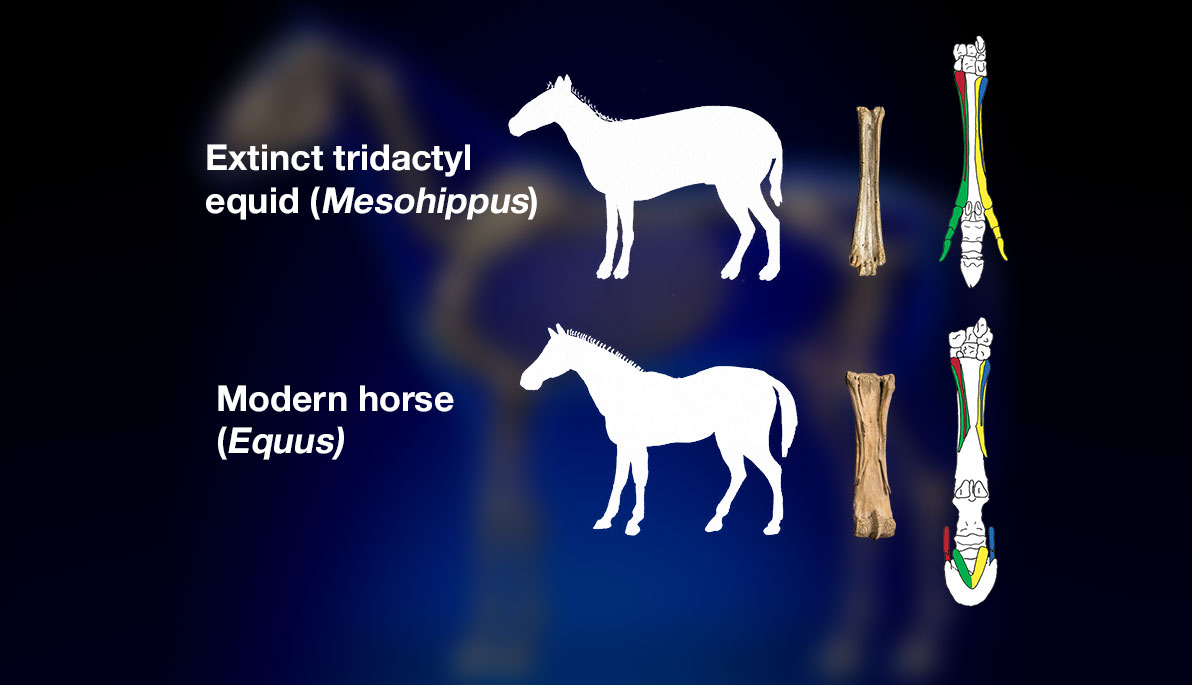

As shown in red and blue, first and fifth digits began to form, but did not fully develop on the side toes (yellow/green) of both the modern horse and its three-toed ancestor, Mesohippus primigenium, which lived 40 million years ago.

Scientists have long wondered how the horse evolved from an ancestor with five toes to the one-toed animal we know today. While it is largely believed that horses simply evolved to have fewer digits, Nikos Solounias, Ph.D., professor in NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) poses a new theory that suggests remnants of all five toes are still present.

Humans and horses are descended from a common ancestor with five digits, but as horses evolved to live on open grassland, their anatomy required a more compact design to enable movement across the hard plains. Until now, scientists believed horses adapted to these conditions: the first horse retained only four digits, while its descendant reduced the number to three. Horses we know today have just a central digit known as the metacarpal—the long bone above the hoof. (Fun fact: the hoof, which many people might mistake for the foot or toe of a horse, is actually the equivalent of a horse toenail.)

For the first time, as published in the January 24 issue of Royal Society Open Science, Solounias and a team of researchers propose that the number of digits was not simply reduced as the horse evolved, but rather, that all five digits merged to form compacted forelimbs with hooves.

“With a distinct surface from the metacarpal, we know the splints [small bones found along the outer sides of the metacarpal on modern horses] on today’s horses to be the remnants of the second and fourth digits,” said Solounias.

Currently, scientists accept that splints are partially formed remnants of second and fourth digits. These fragments, which taper mid-way down the bone, were inherited from an earlier ancestor, but ceased to develop into fully formed digits in modern horses. While the NYITCOM researchers note that this explanation of the second and fourth digits is viable, they argue that it is incomplete and fails to account for the animal’s first and fifth digits.

“These partially formed digits also appear to contain their own elevated surfaces which hold additional evolutionary clues,” said Solounias. “We find these ridges, found on the posterior of each splint, to be the partially formed remains of the first and fifth digits, which were once connected to the cartilages of the hoof.” This revelation indicates that the first and fifth digits were not lost via the evolutionary process, but rather attached to their neighbouring second and fourth digits. The team contends that fragments of the “missing” digits can be found in the form of ridges on the backside of the splints.

“While the horse’s lineage is classically described as having evolved from four to three toes, and eventually one single toe, we show that its extinct ancestors exhibit the reduced toes both at the wrist and at the hoof,” added Melinda Danowitz (D.O. ’17), co-investigator in the study. “These findings show that today’s horse is not truly monodactyl, and earlier ancestors were not in fact tridactyl or tetradactyl, that is, three-toed or four-toed.”

Solounias first considered this theory in 1999 while studying fossil evidence from an eight-million-year-old horse known as Hipparion primigenium. The famous Laetoli footprints in Tanzania demonstrate Hipparion walked alongside early humans, and that it possessed three digits. However, Solounias noticed that the bottom surface of Hipparion’s fossilized forelimb appeared to be divided in five sections, as though the small toes had bonded together. After further studying images of the Laetoli footprints, he confirmed his finding in several of the impressions, and considered that Hipparion not only had five compacted toes, but likely passed this trait on to its descendants.

“Interestingly, we not only find hints of the missing digits on the modern horse, but also its ancestors, such as Hipparion and Mesohippus, two species believed to have three toes,” said Solounias.

Further research also revealed neurovascular evidence in support of the five-digit theory. Dissections of modern equine fetus forelimbs show a greater number of arteries and nerves than would be expected in a single digit.

“If today’s horse does indeed have one digit per forelimb, we would expect each forelimb to have a total of two veins, two arteries, and two nerve bundles,” said Danowitz. “However, our dissections found between five and seven neurovascular bundles per forelimb, suggesting that additional toes begin to develop, but do not become fully differentiated.”

See coverage: