News

Q&A: Kevin LaGrandeur on Monsters, Mad Scientists, Mary Shelley, and Mel Brooks

March 28, 2018

Kevin LaGrandeur

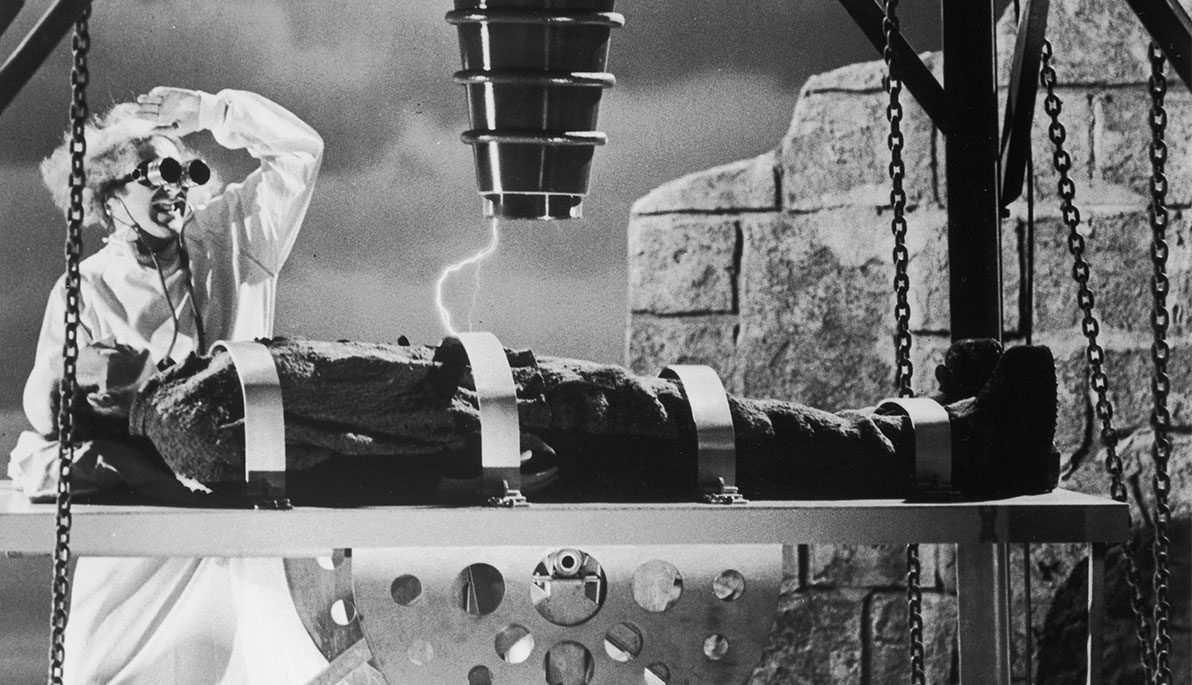

Pictured: American actor Gene Wilder stars as the grandson of the original Frankenstein, with Peter Boyle (1935 - 2006) as the new monster in the Mel Brooks film Young Frankenstein. Much of the laboratory equipment was originally used in the 1931 James Whale film version. (Photo by 20th Century Fox/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Two centuries ago, 20-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley published what would turn out to be one of the most influential, genre-bending novels of all times. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus continues to fascinate and terrify readers and influence artists, scientists, philosophers, and others who are pursuing the cutting-edge in a modern era. Kevin LaGrandeur, Ph.D., professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences, counts himself among those who are both fans and scholars of the novel and its various offshoots. Recently, he had the opportunity to take his exploration of Frankenstein one step further by interviewing the iconic Mel Brooks, who wrote, directed, starred, and produced—you guessed it—the classic comedy Young Frankenstein (1974). His interview with Brooks, “Frankenstein, Young and Old: An Interview with Mel Brooks,” was included in Frankenstein: How a Monster Became an Icon: The Science and Enduring Allure of Mary Shelley’s Creation, a collection of essays published in tandem with the 200th anniversary of the novel.

The Box sat down with LaGrandeur to talk monsters and their masters, comedians and their creations, and how the science and storytelling of the early 19th century ties into teaching and learning in the early 21st.

Before we talk about the interview with Mel Brooks, tell me about your experience with Frankenstein.

I had seen a number of the movies—like Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein—and then I studied the novel as a graduate student. Since then, I’ve been teaching it in various classes. The novel is great in so many ways—including as a proto-science fiction story. The whole backstory about how it was written is also amazing. [The story goes that 18- year-old Shelley was on a trip in Italy with her husband, Percy, and Lord Byron. They challenged each other to tell scary stories, and when Mary told her story, the other two encouraged her to write it down. The result was Frankenstein.]

What aspects of the novel do you focus on when you’re teaching?

I like to focus on ethics and responsibility. What pops out to me in the novel is that Victor Frankenstein basically abdicates any responsibility he has for his creation. He does this incredible scientific feat…but he neglects to think about the fact that it’s not just an experiment on a table—it’s a living creature. Frankenstein is repulsed by his creation as soon as it wakes. And so he abandons it; then it runs off and is freed upon society.

The students [who haven’t read the book yet] think that it’s going to be a horror story. They aren’t prepared for how sophisticated it is. In class, we talk about why Frankenstein might have been repulsed. We focus on modern scientific interpretations of it and the consequences that come up when Victor Frankenstein abandons [the monster], and then it runs away. I ask the students to analyze the ethics of that and the consequences that Frankenstein is ignoring.

So tell us how this interview came about.

I’m good friends with physicist Sidney Perkowitz [the author of the book]. He reached out to me to ask if I knew anyone who would be interested in contributing chapters to this book he wanted to do [on the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein], and I said, “Me!” Since it’s also the 40th anniversary of Young Frankenstein, I thought it would be really interesting to interview Mel Brooks and have him look back on his movie and how it reflects the story.

What was it like to interview Mel Brooks?

It was exciting! I tried really hard not to be nervous. He said, “Now remind me again what you’re doing?” So, I explained who I was and that I was writing a chapter on a book on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. And he said, “Oh. Okay great. You're going to have the best chapter in the book!”

I had all these questions written down, I was hoping for 20 minutes, but he just took off telling stories. He’s a real talker and raconteur. And he started telling stories and they were answering all my questions. I basically took the advice of my father-in-law (who is a biographer) who said, “Whatever you do, just let him talk and let it be about them.”

And here he was, 90 years old, and hasn’t slowed down a bit. He’s still funny, still sharp, could remember everything about the movie. It was every bit as fun as you could imagine. I’ve always loved [Brooks’] movies, so I was really intrigued by his discussion of how the movie got made…and the intricacies of how things work in Hollywood—it’s just mysterious.

That's interesting—how so?

It’s fascinating how much connections matter in Hollywood. The movie cost $2.2 million to make and grossed $86 million. It was a huge success by any measure, and it’s a classic. He had connections and that’s how he finally got what he wanted. [Brooks originally pitched the movie to Columbia Pictures, but they would only give him $100,000 less than the budget he needed and wouldn’t let him do the picture in black and white. Brooks then went to his friend Alan Ladd, Jr., at 20th Century Fox, who let Brooks make the movie he envisioned.] That was really eye-opening for me. It says a lot about society, not just Hollywood. When I started in academia as a grad student, I thought it was a meritocracy…but what I’ve found is it’s actually a business. It’s who you know as much as what you know.

How do you prepare for an interview like this?

The title I came up for the interview was “Frankenstein Old and Young.” I thought a lot about Shelley and Frankenstein—and I did a lot of research on Brooks’ making of the movie. I had to structure the essay so that it was pertinent to the 200th anniversary of the book, so I thought about what would make those two things coherently go together. Before I did the interview, I watched Brooks’ previous interviews on Young Frankenstein going back to the 1970s. [I wanted to focus on] how do you see your film in light of the story and its anniversary, and how do you see your film in hindsight 40 years later?

What was his take on that question?

Brooks said the whole point that he and Gene Wilder [the actor who played Victor Frankenstein in the movie] had agreed on was to make their movie un-scary and to make fun of the scariness of the original movie [from the 1930s]. So that’s why the creature and the creator are friendly at the end of the movie (versus being enemies) and why the movie ends up on a high note with the creature having this mind meld with Frankenstein.

My own take on the movie is that Shelley is in the background and comes out really only in certain scenes, like the last one where the creature gives a soliloquy. That’s very similar to what happens in the book, except the creature in the book is mainly bemoaning its own fate and how its fate has been made miserable by other human beings. He’s like a Shakespearean tragic character—gifted but does all the wrong things at the wrong times. I always thought the book should have been titled The Tragedy of Frankenstein’s Creature.

Any other favorite anecdotes from the interview? One of the funniest things was when I asked, “So if Mary Shelley were here today, what would you say to her?” He said, “Well, I would thank her for writing such a wonderful story and tell her how much I admire her—and I would cut her in for a third of the profits of the movie.” [laughs] That’s how it goes in Hollywood!

Read LaGrandeur’s interview with Brooks in Frankenstein: How a Monster Became an Icon: The Science and Enduring Allure of Mary Shelley’s Creation, or listen to his WGN Radio interview, “Is Artificial Intelligence something we should worry about?”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

By Julie Godsoe

_Thumb.jpg)