Georgiacetus vogtlensis

Age: 41 million years old, Eocene Epoch

Range: This whale inhabited the coastal waters of what is now the Southeastern United States. Specimens of Georgiacetus have been found in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

Size: Estimated to be 11 feet in length.

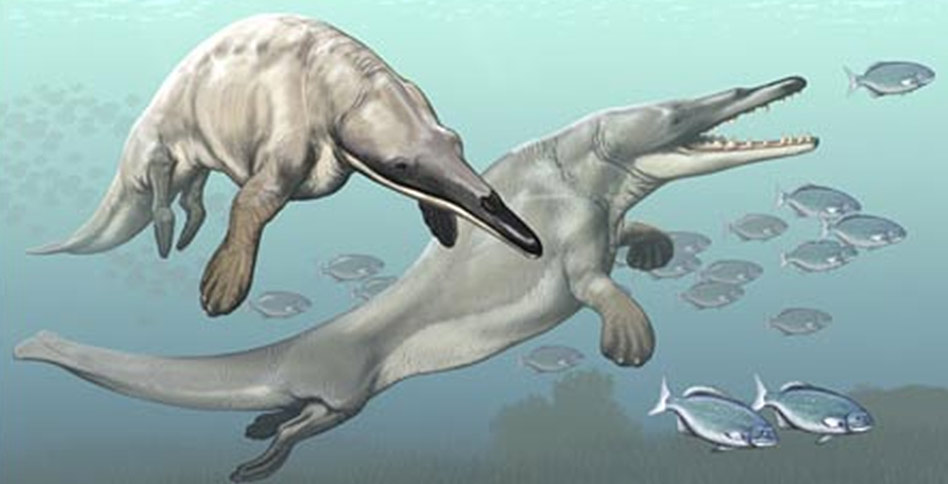

Anatomy: Georgiacetus looked very different from living cetaceans. Its blowhole was still near the tip of its snout, it had heterodont dentition (incisors, canines, premolars, and molars), had a relatively small brain, a large pelvis, and large hindlimbs, although their exact size remains speculative.

Locomotion:

Unfortunately, very little of the tail of Georgiacetus is known, which makes it very difficult to interpret how well this cetacean could swim. Recently, Uhen (2008) has suggested that Georgiacetus lacked tail flukes, based on a partially preserved caudal vertebra of a protocetid from Georgia. However, it is uncertain whether this specimen can be referred to Georgiacetus and whether it was actually situated in the fluke-bearing portion of the tail. If Georgiacetus did not have a fluke, it likely swam using alternate hindlimb paddling or spinal undulation as is seen in otters, which employ the hindlimbs and/or tail as a propulsive surface.

Unlike many earlier cetaceans, Georgiacetus lacked a solid contact between the vertebral column and the pelvis. In fact, all of the vertebrae in the hip region are separate, indicating that this early whale lacked a sacrum. Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that Georgiacetus could not have supported its body weight on land. Further evidence that Georgiacetus was an obligate marine mammal is that all specimens have been found in marine sediments and that isotopes in the teeth suggest that it ingested saltwater instead of freshwater.

Sensory Abilities:

The eyes of Georgiacetus are normally proportioned, indicating vision was an important sense. However, it lacked stereoscopic vision, suggesting that it may have located its prey with sound, either passively or with a rudimentary system of echolocation.

The ear region and jaw of Georgiacetus indicate that it was at least partially adapted to underwater hearing. In modern odontocetes, sound travels to the ear through a large fat body lodged in the lower jaw, instead of via the ear canal. This system works particularly well in water because the density of fat and seawater are similar. If the densities were very different, than a substantial fraction of the sound waves propagating through the water would have been reflected instead of transmitted. Georgiacetus has a large canal in the lower jaw, suggesting this method of hearing through the lower jaw had already evolved. The tympanic bulla, the cup shaped bone that encloses the ear space inside the skull, is also very thick and dense. This anatomy has been interpreted as part of the mechanism by which sound waves traveling in water are conducted to the inner ear. Land mammals use a different method that involves vibration of the middle ear bones, the stapes, incus, and malleus. Unlike many extant cetaceans, Georgiacetus retains a wide ear canal, thus it may have still been able to detect airborne sounds when surfacing.

Diet: The large incisors and canines in Georgiacetus indicate that it was either carnivorous or piscivorous. Its long narrow snout, flexible neck, and large space for the temporalis muscles that close the jaw, all suggest that it probably fed in fish.

Author: Summary written by Jonathan Geisler

References Consulted:

Hulbert RC Jr. 1998. Postcranial osteology of the North American Middle Eocene protocetid Georgiacetus. In The Emergence of Whales. Edited by Thewissen, JGM. New York: Plenum Press:235-267.

Hulbert RC Jr, Petkewich RM, Bishop GA, Burky D, Aleshire DP. 1998. A new middle Eocene protocetid whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and associated biota from Georgia. J Paleontol 72:907-927.

Roe LJ, Thewissen, JGM, Quade J, O’Neil JR, Bajpai S, Sahni ST. 1998. Isotopic approaches to understanding the terrestrial-to-marine transition of the earliest cetaceans. In The Emergence of Whales. Edited by Thewissen, JGM. New York: Plenum Press:235-267.

Uhen MD. 2008. New protocetid whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a new cetacean clade, Pelagiceti. J Vertebr Paleontol 28:589-593.