News

Triumph of Technology

November 1, 2016

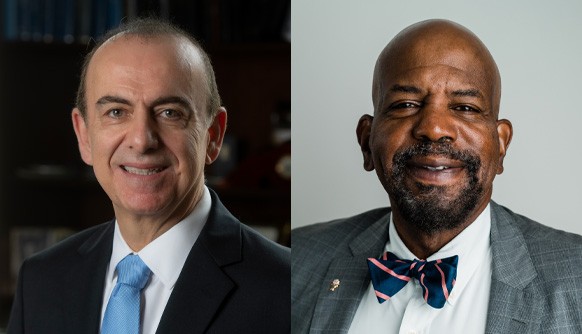

With new technology, new candidates, and new ways to consume media, the 2016 election season has provided no shortage of topics to discuss. Here, College of Arts and Sciences Dean James Simon takes on a few of them.

Illustrations: Mark Allen Miller

Overwhelmed by the Twitter posts that are released every minute of the 2016 presidential campaign? Confused by cable TV hosts who breathlessly shout out new, often contradictory poll results every time you flip through the stations?

You’re not alone.

Whether you are a voter, a campaign strategist, or an NYIT student or professor, the old lessons of political campaigns have not been very useful in this new, amped-up era of politics and the media.

Call it a Triumph of Technology: There is more campaign information (stories, blogs, tweets, Facebook postings, Instagrams, and conventional political ads) bombarding you than ever before. Cell phones give you instant access. Information on the presidential candidates is now a commodity, available anywhere, anytime. On the surface, one story may not look much different than another.

But voters who try to slow down the pace and make the kind of thoughtful, reasoned judgment that we stress in our classes at NYIT may feel like the proverbial generals who rely on the same plan they used to fight the last war, and then quickly find themselves steamrolled by a changed technological environment.

You no longer need to own a printing press to publish your own views. Just in the last four years, newer forms of social media like Instagram, Twitter, and Vine have leveled the playing field and reduced the cost of entry for being heard.

You can pick your preferred technology—print or broadcast, online or social media—and then avoid cognitive dissonance by also picking the political flavor of the news you prefer: Mother Jones is available on the far left, National Review on the far right. Fox News will give you a predictably conservative viewpoint, while CNN is preferred by those who want to watch a news organization struggle to be nonpartisan in its approach.

I am an eyewitness—and sometime participant—in the changes that have turned campaigns upside down since the 1970s. Before becoming dean of NYIT College of Arts and Sciences, I spent a decade as a political campaign reporter for the Associated Press, filing 4,000 news stories in the pre-Internet era.

Back in the day, journalists were still bound by now-quaint traditions of seeking a second source to verify news stories and waiting to get the other side of a story before releasing it. We were taught to “get it right and get it first”—in that order.

The pace of presidential campaigns started to change when I went to work for Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis in 1988. I was part of the fast-response team on environmental issues, needed because reporters were no longer waiting several hours to file complete, verified stories. Complaints started to mount that “speed kills” and that accuracy was being sacrificed for the sake of getting the story first and cleaning up errors later.

With the arrival of around-the-clock cable TV news in the 1990s, endless information sources online, and social media advances, this continuing Triumph of Technology gives each candidate a chance to gain an edge if they can be the first to use a new means of communication in an effective manner.

Republican candidate Donald Trump will be remembered in election history as the candidate who peered into the near future and saw the technological advantages of writing 140-character campaign messages and having them carried instantly via Twitter. He then reinforced the messages by appearing on an endless number of cable TV news shows that were eager to have him elaborate. Who needs paid campaign ads when you can get all the coverage you want for free?

Meanwhile, Democrat Hillary Clinton uses technology to scour the broadcast news landscape, looking for Trump statements that might be used to her advantage. She immediately creates campaign ads reacting to Trump statements and misstatements, getting them out via cable TV for targeted audiences in battleground states. But her misuse of government emails also shows technology is politically neutral—it can help or hurt whatever candidate uses it effectively.

Technology has turned traditional campaigning upside down, and whether you are an NYIT student, a professor trying to keep lesson plans current, or a voter, the pace of change will only quicken.

More reporters are using technology like Google to fact-check candidate claims, often in real time and just seconds after the claim is made. By mid-August, journalists were pushing back at unsubstantiated candidate claims like “the election is rigged” and “FBI Director Comey said my answers were truthful…,” and noting in stories when “there is no evidence that a candidate’s claim is accurate.” Fact-checking services like PolitiFact have applied their “Pants on Fire” designation to both candidates (albeit more to Trump) in an effort to draw attention to misstatements.

As you watch the debates, look to see if the moderators try to hold candidates accountable for any unsubstantiated claims, consistent with the old journalism maxim that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Technology has allowed instant access to more sophisticated polling than ever, but pay attention to whether the survey is of voters nationally (which is of limited value since there are 50 separate state contests) and whether the pollster surveyed residents, voters, or likely voters, each of which will usually give you a different result.

So, how do NYIT professors cope with this tidal wave of information while trying to teach students how to analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and the other elements of critical thinking? How does a school with “technology” in its name help guide students through the intersection of politics, journalism, and media; show them the impact of technological change; and help them become more informed, active citizens?

It’s no easy task. This past summer, our professors had to plan out their fall courses while facing the most unpredictable presidential campaign in U.S. history. Take the following examples:

In Manhattan, Communications Professor Larry Jaffee is having his Journalism 101 students examine how social media allows false campaign information to spread much faster than verified news. While in Long Island, Criminal Justice Professor Andrew Costello’s students are studying laws regarding email and how public servants are bound by legal and ethical guidelines to retain it and maintain separate public and private accounts.

Political Science Professor Michael Izady is looking at the rise of political violence locally and drawing parallels with the rise and spread of fascism in Europe and America. And Philosophy Professor Ellen Katz is taking her students all the way back to Socrates to examine how often or how infrequently critical thinking and support of the facts occur on the campaign trail.

They all hope their grand plans are still relevant when the country staggers to Election Day in this unusual political year, one in which most pundits, including me, start off any new prediction by saying: “Well, I have been wrong about every element of the campaign so far, but I think…”

Four years from now, the technological breakthroughs of 2016 are likely to be as outdated as candidate signs on a voter’s lawn. Technology has turned traditional campaigning upside down, and whether you are an NYIT student, a professor trying to keep lesson plans current, or a voter, the pace of change will only quicken. Get ready for more disruption ahead.

A world-class journalist, expert on environmental issues, and seasoned academic, James Simon, Ph.D., joined NYIT as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences in 2015.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of NYIT Magazine. Read more articles.