News

The Thrill of Discovery

November 14, 2022

Anatomy faculty are conducting cutting-edge research and engaging students to advance knowledge.

Melody Young is sharing a video of a young girl traversing a climbing wall. Young has spent the last year studying how various species—parrots, frogs, chameleons, and sloths among them—climb. A College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) D.O./Ph.D. student, she is a researcher in the lab of Michael Granatosky, Ph.D., assistant professor of anatomy, whose work focuses on animal locomotion. While Young’s dissertation will compare the climbing patterns of various species, she has also expanded her research to humans. An offshoot project compares the climbing gait of neurotypical youngsters to that of neuroatypical youngsters.

“I’m looking to see if climbing can be used as a therapy in children with autism, cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome, who are typically a little more hypotonic in their shoulder and hip girdles,” says Young, who is interested in specializing in pediatrics. “We’re using classical biomechanical measures to see if these patients improve after a training session.”

We’re very focused on getting faculty who are passionate about teaching and research and are keen to serve as research mentors to NYITCOM students.

Jonathan Geisler, Ph.D.

Young originally planned to pursue her doctoral studies in cancer biology. NYITCOM requires its Ph.D. students to complete research rotations in three labs before committing to a lab to conduct dissertation research. She needed to fulfill her third rotation and Young chose the Comparative Animal Locomotion Lab simply because it seemed like a fun opportunity. But the experience changed her path entirely, and Young became the first NYITCOM D.O./Ph.D. student to pursue doctoral study within the Department of Anatomy.

It shouldn’t be surprising. The study of human anatomy is an integral part of medical education, a course taken in the first semester of medical school. In the anatomy lab, NYITCOM faculty introduce students to the intricacies of the human body. Outside the classroom, however, those same professors are engaged in a diverse array of cutting-edge research that propels understanding of human evolution and individual and population health.

“Within the medical school, the anatomy department is unusual in that most of our faculty share a near equal split of research and teaching responsibilities,” says Jonathan Geisler, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Anatomy. “We’re very focused on getting faculty who are passionate about teaching and research and are keen to serve as research mentors to NYITCOM students.”

Setting the Standard, Raising the Bar

Geisler credits Nikos Solounias, Ph.D., chair of anatomy from 1994 to 2006, and a renowned expert on the evolution of hoofed mammals, for charting that course. “He was instrumental in recruiting faculty who could teach anatomy to medical students, but who also did research on the comparative anatomy of both living and extinct species,” says Geisler. “The path that he chose, which aligned with his research interests, has developed its own momentum so that we are an international leader in anatomical research.”

Animal Behavior

Three professors are exploring the origins and evolution of ancient animals, shedding light on millennia-old mysteries.

Simone Hoffmann, Ph.D.

Hoffmann is an expert on the origin and evolution of mammals, with papers describing critical animals from the Mesozoic era (66–256 million years old) from Madagascar and China. In 2020, she was part of a team that named and studied the remains of a prehistoric, possum-sized mammal called Adalatherium. The discovery provides new insight into the diversity of mammals that lived during the time of dinosaurs. In 2018, she was a primary investigator on a successful National Science Foundation grant that funded the acquisition of a micro-computed tomography (microCT) scanner, the centerpiece of the Department of Anatomy's Visualization Center. This instrument uses X-ray technology to create an image of the internal structure of biological specimens at high resolutions. One feature of the grant was to allow external users to use the microCT, resulting in the department becoming a hub for research at New York Tech and across the greater New York metropolitan region.

Matthew Mihlbachler, Ph.D.

Mihlbachler is an expert on the evolution of horses, rhinoceroses, and their extinct relatives, who roamed Earth between 55 million years ago and the present day. He has also made important contributions to understanding how different diets affect the wear of teeth at macroscopic and microscopic levels and how diets and teeth have evolved with climate change. Mihlbachler is also the director of the Academic Medicine Scholars Program, which allows students to spend an additional year at NYITCOM, gaining supervised research and teaching experience. Many of the students in the program have worked closely with anatomy faculty to conduct and publish research on a variety of topics.

Nikos Solounias, Ph.D.

Solounias is an expert on the anatomy and evolution of hoofed herbivorous mammals, specifically giraffes and horses. His research includes how horses evolved from an ancestor with five toes to the one-toed animal we know today and the evolution of giraffes' necks. In a 2015 study, he showed that the evolution likely occurred in stages, as one of the animal's neck vertebrae stretched first toward the head and then toward the tail a few million years later, developing into a remarkably long neck. Solounias has long involved students in his research, resulting in numerous published collaborations on embryology, human anatomy, and mammal evolution.

Supporting that research is a NYITCOM priority. “We’ve made an investment in hiring high-quality faculty and continue to support them by hiring postdocs to assist them and providing faculty the time necessary to conduct research and to apply for grant funding,” says Nicole Wadsworth, D.O., dean of NYITCOM.

As faculty members increasingly publish in prestigious journals, Wadsworth says they help elevate the status of New York Tech within the scientific community. “These publications increase the visibility and reputation of the level of work our faculty are producing,” she says.

NYITCOM’s students are clear beneficiaries. In addition to learning anatomy to prepare for medical careers, participating on high-level research projects—which may or may not have direct clinical applications—helps students experience and understand the complexity of the scientific process.

That’s an experience valued by residency program directors. “Increasingly, research is an important component to a successful residency application,” says Wadsworth. “Residency programs are looking for students with a certain skill set—not necessarily a particular research area, but the ability to participate in research in a meaningful way.”

Granatosky says the scientific process expands the medical education standard by providing students the tools to question what they’re learning. “Most medical students are trained to memorize a lot of information and to treat these findings as facts,” he says. “We researchers deal with the unknown. We’re not researching things that we know exist. The process of discovery helps open the minds of student doctors to the idea that there’s not an answer to everything. And if there isn’t, we can figure it out.”

A Lab of Opportunities for All

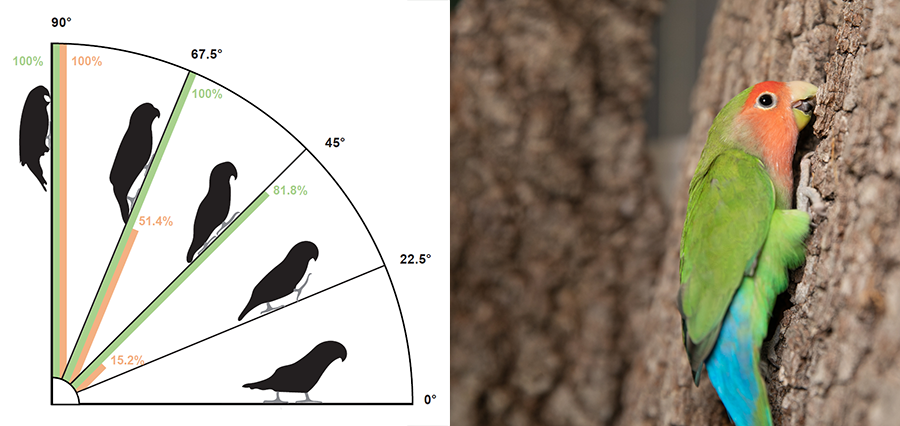

Michael Granatosky discovered that parrots use their head as a third limb when climbing. On the left, the parrots' beaks first contacted the vertical runway when climbing at a 45-degree angle and, then consistently made contact while climbing at a 90-degree angle.

Michael Granatosky discovered that parrots use their head as a third limb when climbing. On the left, the parrots' beaks first contacted the vertical runway when climbing at a 45-degree angle and, then consistently made contact while climbing at a 90-degree angle.

Granatosky is an evolutionary biomechanist who teaches a course for NYITCOM D.O./Ph.D. students called Form and Function, which explores the anatomy and behavior of different species. “We use the same principles of anatomy, but across many different species to understand that structure can inform about physiological function because structure and function are interrelated.”

His research lab explores the same thing, specifically focusing on animal locomotion. Young’s research is a perfect example, already yielding new findings. Young and Granatosky recently published a study in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B that analyzed the climbing gaits of rosy-faced lovebirds, a small species of parrot, which found that parrots use their head as a propulsive “third limb.”

But research opportunities aren’t limited to doctoral students. Granatosky, along with colleague Nathan Thompson, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy, created the Anatomy Laboratory Research Program last year to help facilitate student-led projects. “We have high-performing students who come to us with beautiful ideas, and we are providing the logistical support to make those projects happen,” says Thompson. The program supports several second-year medical students annually on research that involves the anatomy lab in some capacity. The students then recruit first-year students to serve as their research assistants.

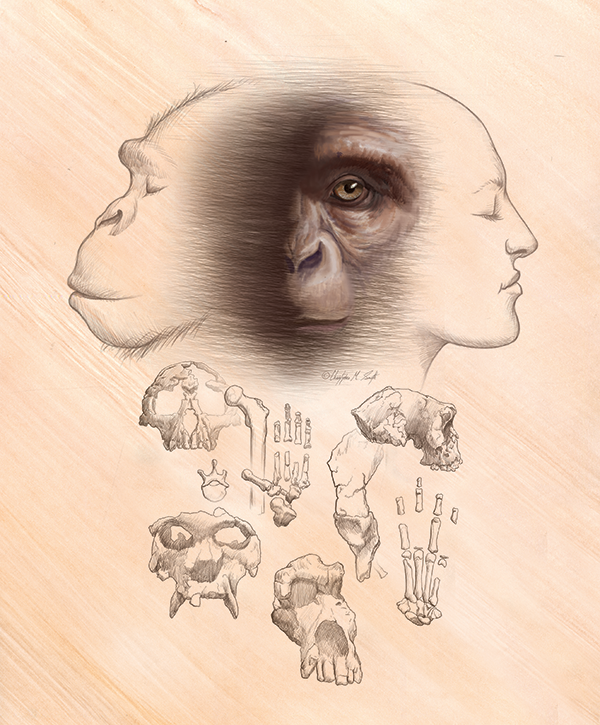

Meanwhile, NYITCOM’s Academic Medicine Scholars Program is designed to give students a feel for academic medicine. Medical students in the program spend an additional year conducting research and teaching, earning a master’s degree in the process. Many students in the program conduct research with anatomy faculty, including Thompson, an evolutionary biologist whose work with chimpanzees and apes has informed knowledge on humans’ ability to walk on two legs and the human stride. More recently he studied the importance of fossil apes in the study of human evolution. The findings from the research were published in the journal Science in May 2022.

Nathan Thompson's work with apes and chimpanzees has shed light on human evolution as well as humans' ability to walk on two legs and the human stride. Illustration by Christopher M. Smith.

Nathan Thompson's work with apes and chimpanzees has shed light on human evolution as well as humans' ability to walk on two legs and the human stride. Illustration by Christopher M. Smith.Thompson is deviating from this research to take on a new project related to fetal development with third-year medical student Rachel Feltman, who will start the Academic Medicine Scholars Program in January 2023. “Many recent state laws limiting access to abortion use anatomical justifications and statements about embryonic developments that—at face value—are not correct,” he says. The project will survey OB-GYNs, reproductive endocrinologists, and other doctors and researchers who are experts in fetal development to evaluate the accuracy of what Thompson refers to as “anatomical justifications.”

“This is a project that has the potential to have an impact on both the medical and legal arenas,” he says.

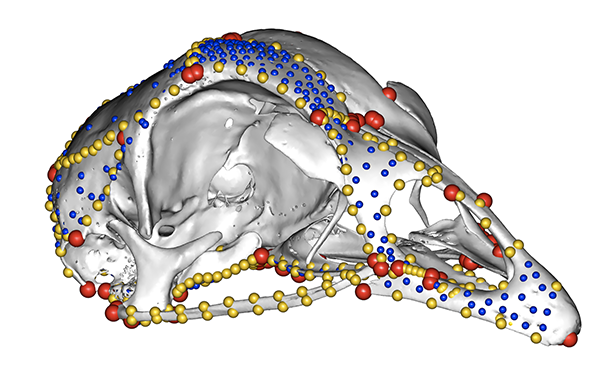

Thompson is not alone in his evolutionary approach to research. Thanks to a prestigious Faculty Early Career Development Program (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Akinobu “Aki” Watanabe, Ph.D., assistant professor of anatomy, is examining how the brain and skull have interacted over millions of years to dictate evolutionary structural changes, as well as the developmental causes and effects of brain-skull interaction using the domestic chick as a model organism. His research may help clinicians prevent and treat future neurological and cranial birth defects, which can cause developmental delays, physical malformations, and even death.

Using data collected from birds and reptiles, Aki Watanabe examines how the brain and skull interacted over millions of years to understand their evolution and development and possible links to neurological and cranial birth defects.

Watanabe teaches human anatomy at NYITCOM and guest lectures in D.O./Ph.D. classes. He also holds a research associateship at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where he earned his Ph.D. in evolutionary biology and teaches classes there on paleontology and geometric morphometrics.

Watanabe uses that technique—a statistical analysis of shape—to collect high-resolution anatomical data on the brain and skull across the tree of life, focusing on reptiles and birds. He is the first New York Tech faculty member to receive a CAREER award, one of the NSF’s most competitive grants, and is expected to receive funding of $710,855 over five years.

Watanabe currently mentors a postdoctoral researcher and seven students on research projects in his lab. Academic Medicine Scholars Sylvia Marshall, Scott Landman, and second-year NYITCOM student Shebin Tharakan have spent two years in Watanabe’s lab, working on high-resolution scans of human eyes, how novel brain shapes emerge, and why snakes and lizards end up with totally different skull configuration. “When motivated students join my lab, I allow them to participate in all the components of their project, from data collection to leading the preparation of a manuscript to be submitted to peer-review journals that the student will be first author on,” says Watanabe. “I was lucky to have had that kind of opportunity as an undergrad, so I try to replicate and pass it on to the next generation of students because having these sort of learning experiences outside of standard coursework can be very meaningful.”

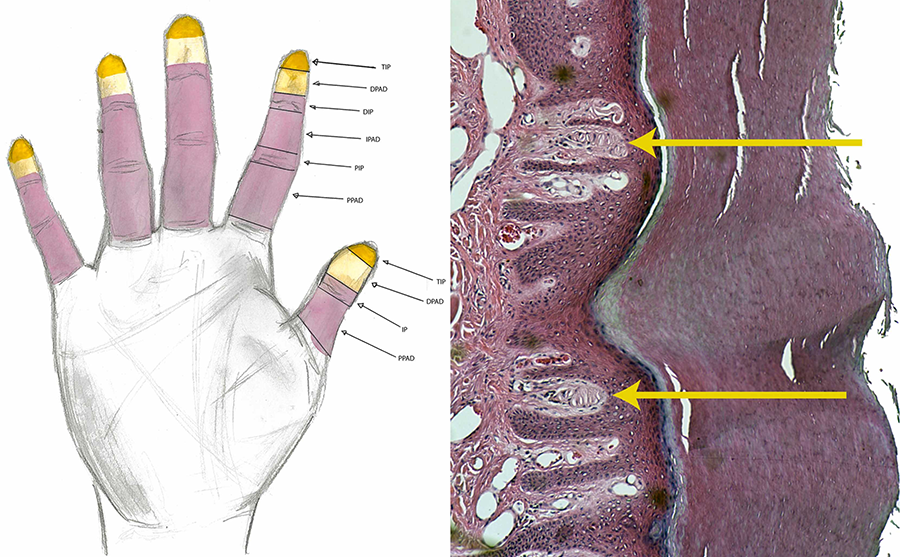

Brian Beatty's research on Meissner's corpuscles may explain why some individuals are more sensitive to tactile sensations than others. Left, a histological image indicating Meissner's corpuscles; Right, a palm and finger view of the regions that were sampled. Illustration by Joseph Ciano.

Brian Beatty's research on Meissner's corpuscles may explain why some individuals are more sensitive to tactile sensations than others. Left, a histological image indicating Meissner's corpuscles; Right, a palm and finger view of the regions that were sampled. Illustration by Joseph Ciano.

Just ask Joseph Ciano (D.O. ’16). As a medical student at NYITCOM, he worked with Brian Beatty, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy, on a project that explored why some individuals are more sensitive to tactile sensations than others. Ciano analyzed skin tissue from the right hand of 16 cadavers under a microscope to document the number of Meissner’s corpuscles present in each finger, finger region (based on distance from the palm), and hand. That study, published in Annals of Anatomy in May 2022, suggests that variations in the distribution of Meissner’s corpuscles may explain why some people are more sensitive to tactile sensory cues—which could be advantageous for activities such as playing the piano, sculpting art, or performing osteopathic manual manipulation.

“Having more Meissner’s corpuscles in the fingers may be advantageous to D.O.s and other healthcare professionals who use palpation to clinically examine and treat patients, as it could enable them to feel subtle differences in the body,” says Ciano, now an emergency medicine physician at Northwell Health.

We have high-performing students who come to us with beautiful ideas, and we are providing the logistical support to make those projects happen.

Nathan Thompson, Ph.D.

The project is one of many Beatty has engaged in with students to make use of cadaver remains after the completion of an anatomy course. Other projects included a study of oral mucosa, which Ciano also conducted, and current research on the surface metrology, or roughness, of skin assisted by Beatty’s “dermatology army” of students. “What we’re trying to do is develop techniques for studying people’s outsides to determine what’s happening on the inside without hurting them, such as making a model of a mole or keratosis on the skin to see if potentially we could develop this into a diagnostic tool for skin cancer.”

Like others, Beatty extolls the experience of research as a way to improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving. But he says the use of human cadavers for research also reinforces to students the value and importance of these anatomical gifts. “If we can maximize the educational and research outcomes for every donation, we’re fulfilling the wishes of those donors that much more,” he says.

Diverse Ideas Advance Knowledge

Shortly after arriving at NYITCOM five years ago, Assistant Professor of Anatomy Julia Molnar, Ph.D., was approached by two Academic Medicine Scholars interested in creating a research project to see if drawing could help students learn anatomy. Molnar, who holds a master’s degree in medical illustration, was a natural mentor. “We put this project together where every week a group of first-year medical students in anatomy would come in the evening and draw structures related to what we were studying and look at anatomy-related art and do a little bit of critique of each other’s work,” she explains.

While the program did not measurably improve anatomy scores, the students enjoyed the experience so much they wanted to keep it going. That effort became ARTery, a popular art and medicine interest group at NYITCOM that continues today. “There’s obviously an aspect of art that is more about wellness and connecting with people on an emotional level,” she says.

Julia Molnar is taking what she learned from the initial iteration of her ARTery project to introduce drawing techniques that may be helpful for students to understand anatomical concepts. Illustration by Eden Alin.

Julia Molnar is taking what she learned from the initial iteration of her ARTery project to introduce drawing techniques that may be helpful for students to understand anatomical concepts. Illustration by Eden Alin.Using what she learned from the initial iteration, Molnar is launching a new research project using art to help students study for anatomy exams. With the assistance of Academic Medicine Scholar Natalia Avery, a member of ARTery, Molnar plans to introduce drawing techniques she believes are useful for understanding anatomical concepts, such as using tracing paper overlays and color coding to learn muscle layers. Students will do all their drawing projects in a notebook that they can use as study material. “We’re trying to take students who wouldn’t necessarily use drawing and give them the basic skill set so that they can,” she says. “When you’re trying to learn something deeply and retain it, being able to translate it into visual representation can be really helpful.”

Molnar’s doctorate is in the field of evolutionary biomechanics, further representing the diversity of NYITCOM’s anatomy faculty, which also includes scholars from the fields of biology, earth and environmental sciences, geology, as well as anatomical science. “When you have people with very different backgrounds, interests, and expertise, interdisciplinary research develops naturally, and we are able to creatively test questions in our own research areas by learning from the approaches of our colleagues,” says Geisler.

That diversity and the collegial spirit of those researchers has been a plus for Young. “One of the strengths of this department, and this lab in particular, is the willingness of faculty to learn alongside students,” she says. “I came in without any experience in this area, and was like, ‘We need to do some human work.’ And although Professor Granatosky had never done human research before, he was willing to dive into the literature with me to figure out how we can make my project somewhat clinically relevant.”

Advancing knowledge while helping students to become intellectually curious professionals is really the goal.

“Research allows students to get a sense that the world is much bigger than their immediate interest,” says Geisler. “Having this broader curiosity is really important, not just to be a scientist, but to be a great physician because you never know when that really hard case is going to come through the door.”

Animal Behavior

Three professors are exploring the origins and evolution of ancient animals, shedding light on millennia-old mysteries.

Simone Hoffmann, Ph.D.

Hoffmann is an expert on the origin and evolution of mammals, with papers describing critical animals from the Mesozoic era (66–256 million years old) from Madagascar and China. In 2020, she was part of a team that named and studied the remains of a prehistoric, possum-sized mammal called Adalatherium. The discovery provides new insight into the diversity of mammals that lived during the time of dinosaurs. In 2018, she was a primary investigator on a successful National Science Foundation grant that funded the acquisition of a micro-computed tomography (microCT) scanner, the centerpiece of the Department of Anatomy's Visualization Center. This instrument uses X-ray technology to create an image of the internal structure of biological specimens at high resolutions. One feature of the grant was to allow external users to use the microCT, resulting in the department becoming a hub for research at New York Tech and across the greater New York metropolitan region.

Matthew Mihlbachler, Ph.D.

Mihlbachler is an expert on the evolution of horses, rhinoceroses, and their extinct relatives, who roamed Earth between 55 million years ago and the present day. He has also made important contributions to understanding how different diets affect the wear of teeth at macroscopic and microscopic levels and how diets and teeth have evolved with climate change. Mihlbachler is also the director of the Academic Medicine Scholars Program, which allows students to spend an additional year at NYITCOM, gaining supervised research and teaching experience. Many of the students in the program have worked closely with anatomy faculty to conduct and publish research on a variety of topics.

Nikos Solounias, Ph.D.

Solounias is an expert on the anatomy and evolution of hoofed herbivorous mammals, specifically giraffes and horses. His research includes how horses evolved from an ancestor with five toes to the one-toed animal we know today and the evolution of giraffes' necks. In a 2015 study, he showed that the evolution likely occurred in stages, as one of the animal's neck vertebrae stretched first toward the head and then toward the tail a few million years later, developing into a remarkably long neck. Solounias has long involved students in his research, resulting in numerous published collaborations on embryology, human anatomy, and mammal evolution.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of New York Institute of Technology Magazine.

By Renée Gearhart Levy

_Thumb.jpg)