News

Running and Women’s Bodies

June 29, 2018

While many people increase their exercise level to boost their metabolism, a recent study by Joanne Donoghue, Ph.D., assistant professor of osteopathic manipulation at NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM), found that female runners who run an average of 30 miles a week actually had a lower metabolism than women running an average of 10 to 12 miles a week.

Joanne Donoghue, Ph.D.

Despite their higher lean body mass, “we found that their bodies basically adapted to being in a constant state of energy restriction,” says Donoghue. An avid athlete herself—she’s run 10 marathons and completed two Ironman competitions—and a registered clinical exercise physiologist with a Ph.D. in nutrition, Donoghue has a natural interest in female runners and metabolism. “When I ran my first marathon in 2001, the New York City marathon was only 10 percent women. Now it’s more than 40 percent across the country. And triathlons are one of the largest growing sports for females,” she says.

Regardless of that increased participation, there’s a lack of research on the physiological impact of running on the female athlete. Donoghue hopes to fill that void with her study on the impact of recreational running on the metabolism and body composition of women.

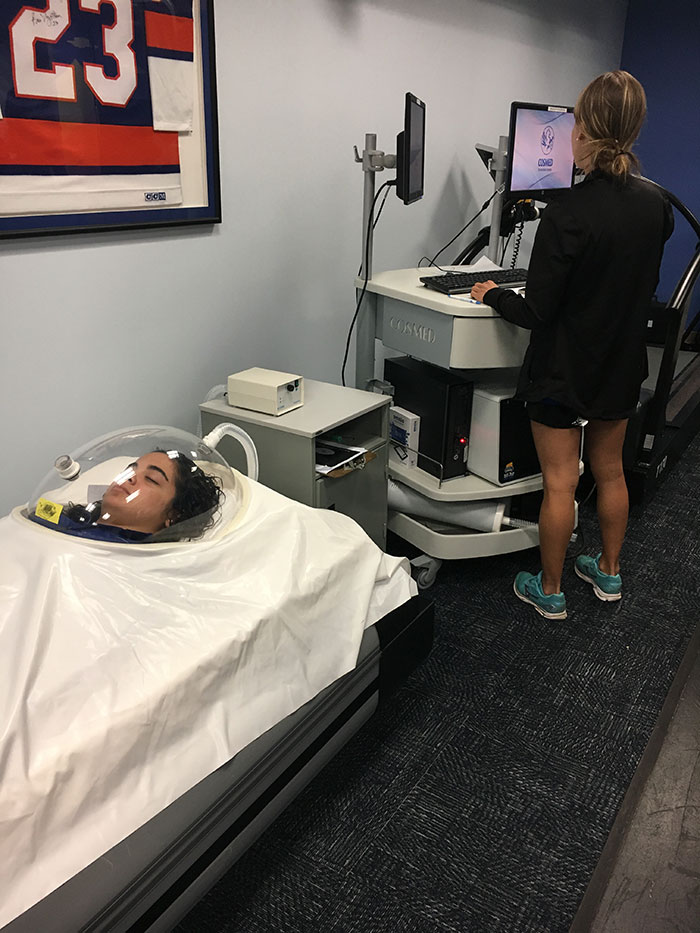

Joanne Donoghue, Ph.D., uses state-of-the-art technology at NYIT’s Center for Sports Medicine to measure the metabolisms of female runners in their 20s.

Her study compared two cohorts of 20-year-old women—all NYITCOM medical students and physical therapy students in NYIT School of Health Professions—middle-distance runners (who run 10 to 12 miles per week) and long-distance runners (who average 30 miles per week). The subjects kept food diaries and underwent tests measuring their oxygen consumption, metabolic rate, and body composition using state-of-the art technology at NYIT’s Center for Sports Medicine.

Second-year medical students Ashley Deluca, Mina Divan, and Courtney Baranek assisted Donoghue with data collection.

“Both groups essentially took in the same number of calories and both groups barely hit their resting metabolic rate, but the long-distance runners expended many more calories and had a huge calorie deficit,” says Donoghue. “What we learned is that, as you increase mileage, you need to make sure you compensate and increase those calories at the same time, or your metabolism is going to slow down.”

Since many of these long-distance runners were, at the time of the study, training for a half-marathon or marathon, Donoghue plans to follow up in eight months to see what changes occurred during their off-season. She hopes to continue the study longitudinally to follow how aging impacts female metabolism and body composition. “We know you lose lean body mass as you age, so it will be interesting to see how recreational running impacts women’s bodies through their 30s, 40s, and 50s,” she says.

This story originally appeared as part of the feature "Bio + Tech = a Healthier Future" in the Summer 2018 issue of NYIT Magazine.

By Renée Gearhart Levy