News

Q&A: Brian Beatty on the Mammalian Fossil Formerly Known As a Dinosaur Bone

August 6, 2018

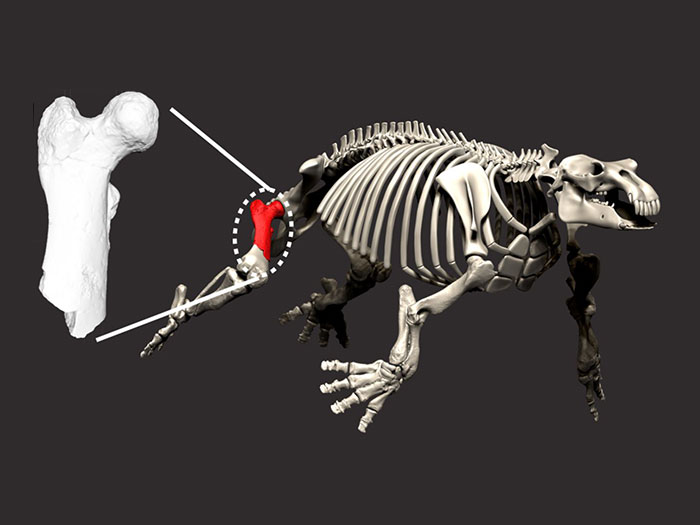

Pictured: An artist rendering of a Paleoparadoxia. Photo courtesy of The Royal Society Open Science journal.

Brian Beatty, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy in NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine, can now add sleuth to his résumé. Beatty along with a team of researchers recently identified a fossil femur believed to belong to a dinosaur as actually that of a Paleoparadoxia, a large semiaquatic mammal that resembled a hippopotamus and lived on the coast of the North Pacific millions of years ago. Fossils of the ancient creature have been found in Japan, Russia, Alaska, and all along the Pacific coast of North America as far south as Baja California Sur.

This is science, and science is about carefully interpreting reality, it shouldn’t be about popularity and attention.

Associate Professor Brian Beatty, Ph.D.

The femur was recently rediscovered in the geological collection room at the University of Tsukuba in Japan and was properly identified by a team of Japanese scientists that also included Beatty. Their findings were published in The Royal Society Open Science journal.

Beatty sat down with The Box to talk about the discovery and the ancient mammal.

What do we know about Paleoparadoxia?

We know quite a bit, mostly because of a few very well-preserved skeletons. They had some very unusual teeth, including upper and lower tusks, and were quite large. Some were about the same size as an Asian elephant and lived in lagoons in what is now Southern California.

What is the “controversy” surrounding the long-lost femur that was found cataloged in the wrong place at the University of Tsukuba?

Perhaps calling it a controversy is a bit exaggerated. This specimen was found some time ago and resides in a local museum in Japan. The story about its finding and identity was made into a newsworthy piece initially, and it was simply identified as a dinosaur bone in that town for many years. But of course, it isn’t a dinosaur.

Who found the fossil? How was it discovered?

The fossil was found near the U.S. Marine Base Camp in Okinawa, Japan, in 1948. The details of exactly who and where it was found were lost.

A Paleoparadoxia skeleton and model of the fossil femur. Photo courtesy of The Royal Society Open Science journal.

Does this finding shed any new light on what is known about the Paleoparadoxia?

This one specimen adds something to the breadth of our understanding of the animal, but the analysis identifying the features of the limb bones that are distinct to this species in comparison to other related animals is the primary benefit of this study.

What do you hope to learn from the fossil femur?

This is a straightforward comparative anatomical study, and one that aims to clarify features of the femur that related species share and do not share. [The femur] is often preserved because of its durability. This isn’t as exciting to most people as the description of a new species or some detailed study of the inside of some unusual animal’s skull, but this is an example of the kind of careful work that is much needed in our field. This is science, and science is about carefully interpreting reality, it shouldn’t be about popularity and attention.

How did you team up with the group from Japan?

This sounds more exciting than it is, but I’m one of the few people that study Desmostylia, the group of animals that Paleoparadoxia belongs to. Kumiko Matsui, Ph.D., a post-doctoral fellow at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, and the lead on this project, asked me to be involved because of that, and she is quickly developing into being just as knowledgeable in this topic as the other four or five people that regularly study them worldwide.

What are the next steps in the study of the Paleoparadoxia?

I have projects to study Paleoparadoxia and related species that include CT scans of skulls to study brain anatomy as well as confocal scans of their teeth to interpret scratches on their teeth and how that relates to their role in coastal ecology.

Is there anything you would like to add?

Just a note of thanks to Kumiko Matsui for involving me in this project. Careful comparative anatomical studies like this aren’t usually popular, and the pressures of perceived success and impact are often deterrents to doing this sort of work for many, especially early in their careers. I value Kumiko’s judgement as to the importance of this sort of work and am proud to have worked with her.

This interview has been edited and condensed.