News

Echo Hunter: A New Fossil Whale Named By NYIT Scientists

August 4, 2016

Photo: An artist’s rendering of Echovenator sandersi, “Echo Hunter,” which used high-frequency hearing and echolocation to hunt (Credit: A. Gennari 2016)

Meet Echovenator sandersi (“Echo Hunter”), the newly-named fossil whale species with superior high-frequency hearing ability. NYITCOM Postdoctoral Fellow Morgan Churchill along with Associate Professor Jonathan Geisler, Ph.D., and colleagues from the National Museum of Natural History in France describe this new species in Current Biology.

An ancient relative of the modern dolphin, “Echo Hunter” could hear frequencies well above the range of hearing in humans. Its super power was aided in part by the unique shape of its inner ear features, which has given scientists new clues about the evolution of this specialized sense. The research pushes the origin of high frequency hearing in whales back in time—approximately 10-million years earlier than previous studies have indicated.

“Previous studies have looked at hearing in whales but our study incorporates data from an animal with a very complete skull,” says Churchill, the paper’s lead author. “The data we gathered enabled us to conclude that it could hear at very high frequencies, and we can also say with a great degree of certainty where it fits in the tree of life for whales.”

“This was a small, toothed whale that probably used its remarkable sense of hearing to find and pursue fish, with echoes only,” says Geisler. “This would allow it to hunt at night, but more importantly, it could hunt at great depths in darkness, or in very sediment-choked environments.”

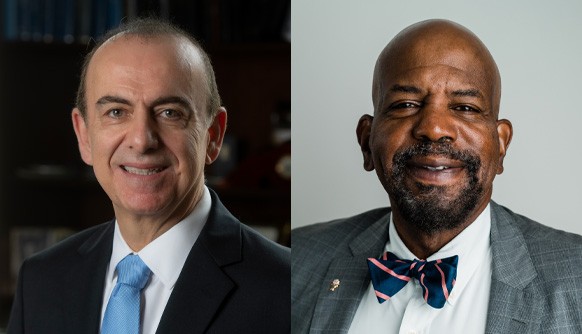

Morgan Churchill, Ph.D., (pictured left) and Jonathan Geisler, Ph.D., with the 27-million-year-old fossil skull of Echovenator

High frequency hearing plays a key role in echolocation (the use of sound waves and their echoes to establish the position of objects). Bats, some whales, and all dolphins use echolocation to hunt.

“Echolocation requires two things to be highly effective,” says Geisler. “First, the animal must have the ability to produce a high frequency sound, and second, it must have the ability to hear and interpret that sound.”

High-frequency sound production and hearing are key, he says, because the combination yields a rich “audio picture” of the surrounding environment. Churchill says the study confirms that most of the specializations associated with high frequency hearing evolved about 27 million years ago—around the same time as echolocation—although a few features evolved even earlier.

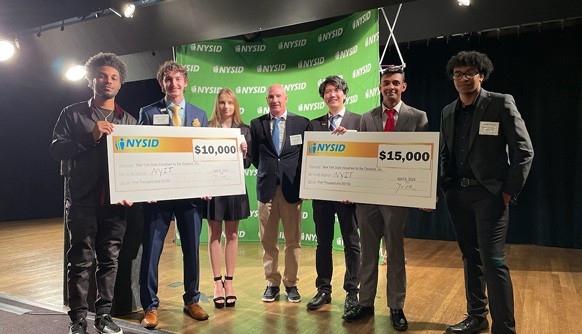

The study is part of an initiative funded by a $220,000 National Science Foundation grant to Geisler and Associate Professor Brian Beatty, Ph.D., to conduct the first wide-ranging study of cetacean skull development in nearly a century.

To learn more about Echovenator, Churchill and colleagues studied a 27-million-year-old skull discovered in South Carolina in 2001. By analyzing the bony support structures of the inner ear membranes, along with other measurements of the inner ear, the researchers concluded that the whale had ultrasonic hearing capabilities

The semiaquatic ancestor of whales (which made earth its home about 60 million years ago) had a limited ability to hear high frequencies. However, Geisler notes that statistical analyses of fossils in the study led researchers to conclude that some degree of high frequency hearing evolved before echolocation and then became even more specialized in modern toothed whales. Baleen whales, which do not echolocate and developed to hear low frequency sound, lost some of these initial specializations for hearing high frequency sound.

The current study, Geisler adds, may help scientists ultimately distinguish what inner ear features are needed for whales to hear high or low frequency sounds. Churchill says fossil studies also allow scientists to understand the evolution of intelligence, how body sizes changed, and characteristics of the surrounding habitats of various whale ancestors.

“Knowing when and how echolocation evolved is a critical step in our project, and we are studying how the evolution of echolocation influenced the evolution of skull shapes in cetaceans,” says Geisler.

Read the study on Current Biology.

Media Coverage:

- The New York Times: An Ancient ‘Echo Hunter’ Provides Clues on Whale Evolution

- Inverse.com: Awesome Ancient Whale Had Ultrasonic Hearing

- The Christian Science Monitor: Fossils hold hidden clues to the evolution of whales' incredible hearing

- Reuters: Hear! Hear! Exquisite fossils preserve ear of prehistoric whale

- Red Orbit: The Echo Hunter: A newly discovered ancient whale with amazing hearing

- Phys.org: Echo hunter: Researchers name new fossil whale with high frequency hearing

- Daily Mail: Fossilised whale skull reveals that the creature's incredible ultrasonic hearing evolved 27 million years ago