News

Borrowing Landscape

August 11, 2016

A collaboration between two architects influences a body of research around structures, light, and landscapes.

Photo (top): Le Corbusier’s Couvent de La Tourette – East Facade.

THE SUN WAS ABOUT TO SET in a small vale in Eveux-sur-l’Arbresle, a town in southeast France where the Rhône and Saône rivers unite. At this grassy edge of the country’s Beaujolais wine valley, light glinted on a structure of austere and undulating concrete forms: Le Corbusier’s Couvent de Sainte-Marie de la Tourette, known simply as La Tourette. On this evening, during the summer solstice of 1994, architect and tenured NYIT Associate Professor David Diamond had just finished dinner and decided to take a walk. He strolled into the church. The next moments would define his career path for years to come.

“I started to see something amazing,” recalls Diamond. He snapped a series of photos recording the solstice sunset. “This bar of light coming through the window began to travel toward the altar wall, where it traced a diagonal path before escaping through an upper window. At that moment, another bar of light came through a hidden window, illuminating the cross and turning it red. The ceiling glowed. This incredible thing was happening that no one had ever described or written about before, and I needed to record it.”

Le Corbusier was a pioneer of 20th century modernism in architecture and painting. He often adapted forms from his still-life paintings to his architecture, and from his architecture to his paintings. His design for La Tourette (made in the 1950s and built in 1961) demonstrates this. “I’m interested in the ways Le Corbusier related his architecture to the world outside,” says Diamond. “One way is how he admitted light into his work.”

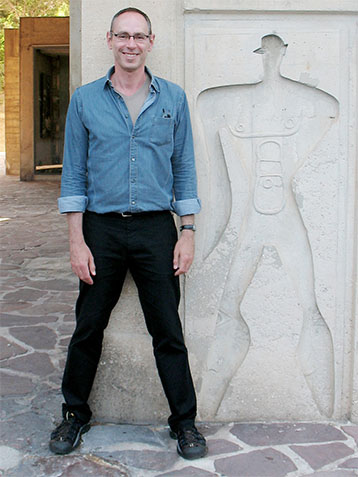

David Diamond at Le Corbusier's Unité d'habitacion in Marseille, France.

Diamond returned to New York intent on re-creating what he had captured in those photographs. He continued his research on Le Corbusier in tandem with his teaching career, and in 2000, turned to then-NYIT architecture student Esteban Beita (B.Arch. ’03) for help.

Diamond, who served as chair of the Department of Architecture at NYIT Manhattan from 1998 to 2011, met Beita when he first arrived on campus to begin his studies. Diamond reviewed his portfolio and noted his dexterity with digital media. Their ensuing collaboration would prove pivotal for both men.

Beita built a computer model that simulated lighting effects at La Tourette on certain days and times. Ultimately, he helped Diamond to develop the tool needed to demonstrate what he witnessed years before.

“I was able to reproduce and disseminate what I saw,” says Diamond, who would return to La Tourette again and again, often with NYIT students. (He also directs some of the School of Architecture and Design’s summer study abroad programs, which bring students to different locations to explore architecture up close.) He most recently presented his research in Paris at the Société Française des Architectes’ (SFA) spring 2015 colloquium; this past November, the SFA published his essay “Borrowing Landscape and the Enigma of Corbu” in their architectural journal Le Visiteur. Visuals of Beita’s daylight simulations accompany the essay.

“Borrowed landscape, borrowed scenery, or shakkei, as it is called in Japanese, refers to the incorporation of distant views into the scenography of formal gardens,” writes Diamond in his essay. “It involves the foreground framing of distant vistas, and the selective blocking of the middle distance to obscure unwanted features from view.”

Diamond’s collaboration with Beita introduced the younger architect to the allure of those different viewpoints and would influence his future steps thousands of miles away and to the opposite side of the world. (Story continues below.)

Le Corbusier’s Church at La Tourette. Sequence 1: Digital simulation at sunset (wide view). Sequence 2: Digital simulation at sunset (crucifix). Sequences 3 and 4: Live footage from June 2014. Live video footage by David Diamond and digital animation by Esteban Beita.

Seeking Space

Beita’s journey actually began independently of his work with Diamond. He was browsing the library at NYIT’s Manhattan campus and saw a book on Japanese architecture. The ancient temples and tea houses beckoned from the pages. They captured his imagination for reasons he couldn’t quite describe, in the same way that Diamond was and continues to be drawn to the works of Le Corbusier. Some things Beita knew for certain: how the beauty of each temple and tea house tied closely to its nearby gardens, and how the spaces seemed to change with the shifting seasons.

“I became interested in how outdoor and indoor spaces work together,” says Beita, who later saw this effect in action while working on 3-D light simulation models for Diamond. “From there, I set my goal to get to Japan.”

Beita arrived in Japan in 2005. He received the Monbukagakusho Scholarship, which paid for his master’s degree and Ph.D. in architecture from the University of Tokyo. He stayed in Japan for five years, during which time he completed his degrees and focused his doctoral thesis on documenting the Bosen Tea Room in Koho-an Temple, designed in the 1600s by Kobori Enshu.

“The Bosen Tea Room is part of a temple considered a national treasure,” says Beita. “Monks live there. Unless you get a private tour or request access in advance, you can’t go in. It took me two years to get permission to enter.”

When Beita finally entered the temple, he brought an antique Nikon camera (1955 film camera) and a more current digital Canon with an 8 mm fisheye lens for capturing wide-angle views, as well as sketch pads for jotting down dimensions and building details. Most importantly, he brought his curiosity.

“I talked to the monks first,” says Beita. “I wanted to know their experiences and any special moments I should be looking for.”

One of those moments was the way light rippled, like waves, on the temple’s exterior during early afternoon in summertime. Beita knew Enshu had grown up near a lake and may have been inspired by water, however, the Bosen Tea Room is in an area far from any lakes or the sea.

“I learned the rippling effect occurs because of a small water basin in front of the tea house,” says Beita. “By later doing a 3-D model, I could prove this.”

Beita also photographed the surrounding landscape and noted the coordinates of trees, bushes, and gardens to be included in his models.

“To know what happens from morning to evening within a space is hard to see unless you live there yearround,” says Beita, who only had a couple of hours in a single day for his fact-finding mission. “I could see at what point the light hit the space. Is this the architect’s intention or a coincidence? Making the 3-D models helped me to figure it out.”

At the time, Beita made his models using AutoCAD and 3-D Studio Max software with a V-ray plugin for rendering photorealistic materials. The process entailed piecing together data on the space’s dimensions with his photos taken from many angles to create a single accurate reproduction of the entire Bosen Tea Room, outer landscape included.

“I looked at how the space works from morning to evening throughout the whole year, through spring, summer, fall, and winter,” Beita says. And the rippling effect in question? His 3-D models narrowed down the lighting effect to between 1 and 2 p.m. in summer. “Japanese spaces are always different,” Beita says. “No matter which season you go, you can have your personal experience.”

From Tokyo to New York City

While Beita and Diamond are fascinated by different architectures and time periods, both believe in the interplay of a built structure within a given topography—a visual poetry that can merge a piece of architecture with the world outside: gardens, terrain, the changing seasons, and solar events. The effect can transform a place into something else: a metaphor, or a framed tableau. It can collapse time and space or alter them, like a painting cropped by an artist for his canvas, or an optical illusion captured from a particular vantage point.

My research has to do with how architects conceive projects, and it overlays with my teaching interests in helping students to translate their ideas.

David Diamond

Beita and Diamond have individually shared their research with the NYIT community as part of the School of Architecture and Design’s lecture series. Beita returned to NYIT as an adjunct professor of architecture in 2012 (he is also a full-time assistant professor of architecture at New York City College of Technology), and presented his photographs of the Bosen Tea Room and other temples at the 2015 NYIT Gallery 61 exhibition, “Together in Harmony: Images of Japanese Architecture.”

The two architects plan to visit La Tourette together soon and use a 3-D laser scanner to better document the convent. For now, their focus is on guiding students in New York to think critically about how they approach their craft in relation to the contexts in which their projects are designed.

“My research has to do with how architects conceive projects, and it overlays with my teaching interests in helping students to translate their ideas,” says Diamond. Students in his studio course Design Fundamentals II choose an image of a painting and are asked to envision it in three dimensions.

“We start with a fact, a mark on a canvas,” says Diamond. “What does it mean? Is it a wineglass or a piece of fruit or a guitar? Then we look at what else it could be. Could this be a tabletop and a guitar at the same time?”

NYIT student Robert Nafie took Diamond’s studio course. During a midterm review in March, he presented his 3-D interpretation of Las Meninas, the 1656 masterpiece by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez.

“I looked at spatial relationships in the painting and how they interact,” says Nafie. “I struggled to create a model that you know is from the painting but also showed these compositional relationships.”

The studio is a safe place for students like Nafie to talk about their creative ideas and challenges. “In addition to learning concepts and skills, students develop the ability to evaluate and critique,” Diamond adds.

Ultimately, Diamond and Beita teach architecture students to contemplate the mysteries of architecture—whether in the form of an island temple or a convent in the countryside. The beauty of architecture is just as much about what the eye sees, as it is about the inner life of the person who sees it.

“I tell my students that, every day, they are building the person they will become,” says Diamond. “I tell them to keep their aspirations high and directed toward being better decision makers.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of NYIT Magazine. Read more articles.

Photography and simulation courtesy of David Diamond and Esteban Beita.

_Thumb.jpg)