News

Q&A with Amanda Golden: A Study in Archives

December 6, 2017

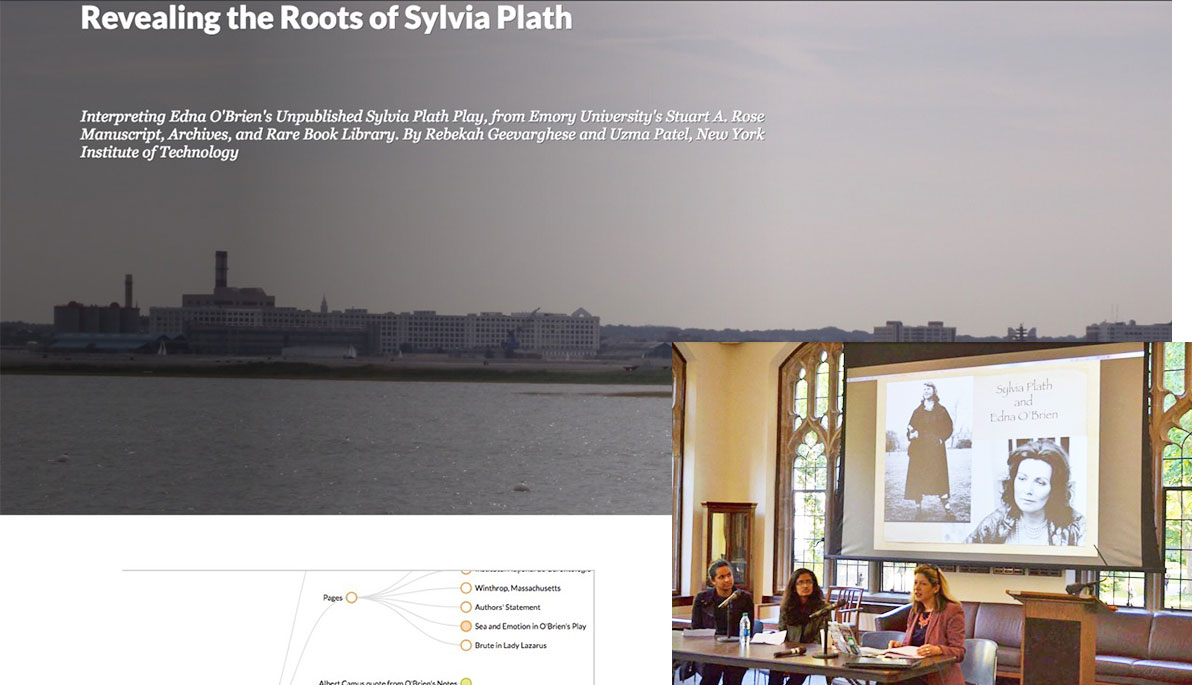

Above left: a screenshot of the team's presentation using the app Scalar. Inset: (left to right) Uzma Patel, Rebekah Geevarghese, and Amanda Golden present research on Edna O'Brien and Sylvia Plath at the Transnational Print Culture Conference.

Amanda Golden, Ph.D., assistant professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences, often blends technology and 20th century literature in her classes. Her combination of expertise is the perfect match for NYIT. After receiving her Ph.D., she did two post-doctoral fellowships: one in poetics at Emory University’s Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry and another, the Brittain Fellowship, in digital pedagogy at Georgia Tech. Golden’s other primary area of expertise involves studying the archives of writers (in particular, the author Sylvia Plath). This year, she invited two of her students, Rebekah Geevarghese and Uzma Patel, to assist her in researching writer Edna O’Brien’s unpublished play about Sylvia Plath. By working with scans of O’Brien’s text and handwritten notes (the originals are in Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library), the team explored O’Brien’s creative process and used an emerging open-source, media-rich publishing app called Scalar to visualize their findings. Following a summer of intense work, the team presented their findings at Fordham University’s Transnational Print Culture Conference in October.

The Box recently sat down with Golden to talk about her research, the move toward digital archives, and the process of collaborating with students.

The movie Possession (based on the novel by A.S. Byatt) focused on scholars who uncover the secrets of two Victorian poets by looking at their letters. Is the thrill of discovery something that drives you in your research?

Possession is an exciting representation of what scholars who work in archives try to do. It involves retracing a lot of earlier steps, and realizing that earlier scholars had some pieces and not others. It is a long process, working with archives, and you often feel that you will never fully understand [the subject]. Researchers also interpret things differently over time. Our ways of reading change, so an archive has a lasting ability to be reinterpreted by different scholars.

What discoveries did you make over the course of your Edna O’Brien research?

While the first question many would ask is whether it is a good play, my objective was not to judge whether it was good or bad, but instead to better understand what O’Brien was trying to do and how the manuscripts and typescripts that remain reflect her strategies as a writer.

When I was finishing the paper for the conference, I realized that the play was probably a screenplay. There were voiceovers and references to a camera. It turns out that O’Brien wrote other screenplays, so that was an interesting discovery. I was also trying to understand why O’Brien never produced it. At the time, there was a big lawsuit about the film of The Bell Jar, so I also thought that if she intended this as a screenplay, the media attention may have dissuaded her from moving forward.

Has the digital landscape altered the nature of your research?

Archives in particular are a rich field for digitization. It is better to work with the original items, but the digital side is inevitable and exciting because it can bring more people to more materials. Even museum websites have added images of materials that would not normally be on display.

I include different kinds of digital archives in my classes, from having students learn about the time periods in which our texts are set by searching online newspaper archives to investigating Virginia Woolf’s composition of To the Lighthouse using Woolf Online (which includes images and transcriptions of her manuscripts). When I worked with students this summer [on the Edna O’Brien research], they saw my pictures of the notebooks closed and open, but it is not the same thing as working with the originals. It took them a little while to get acclimated and imagine what the materials looked like in real life.

How did your students assist you with your research?

My students were very careful. They took two classes with me (Foundations of College Composition, with the theme Apple and Microsoft: 1975 to the Present and Foundations of Research Writing, with the theme Writing New York); they were skillful in distinguishing all the different purposes and the context of the materials. Because O’Brien was writing a play about Sylvia Plath…my students read Plath’s novel The Bell Jar, her poems, and excerpts from her Unabridged Journals [in addition to O’Brien’s manuscripts and typescripts of her play]. They made really smart connections—connections that I would not have seen because I was more familiar with Plath’s work.

The students also developed an understanding of Scalar, which was new to me. Scalar is meant for long-form digital publishing and there have been all sorts of experiments with using it. The students picked the theme of the sea, and visually represented it through the presentation. Other scholars have written about Plath and the sea, but the students were not aware of that. They are good readers, and they saw the thread—I was impressed.

The three of you used Scalar in your presentation at the conference. How did that go?

It was interesting because the audience was mostly made up of faculty and students studying Irish literature. Some of the faculty members were interested in Scalar as well, but had not used it before. It was fun to see them learning from my students’ experiment.

What was it like attending the conference with your students?

It was great that the students had the opportunity to present in front of a professional audience. In fact, I believe they were the only undergraduates who presented. They had a lot of energy for the project, and others at the conference were impressed with what the students were able to achieve.

(left to right) Uzma Patel, Amanda Golden, and Rebekah Geevarghese on Fordham University's campus in the Bronx, NY, for the Transnational Print Culture Conference.

Golden’s book about the libraries of writers, Annotating Modernism: Marginalia and Pedagogy from Virginia Woolf to the Confessional Poets, is forthcoming from Routledge.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

By Julie Godsoe