Messapicetus spp.

Age: 9-13 million years old, Miocene Epoch.

Range: Two species of Messapicetus have been described: Messapicetus longirostris from Italy and Messapicetus gregarius from Peru. Additionally, an incomplete skull (Messapicetus sp.) from Maryland is known, indicating that Messapicetus inhabited the North Atlantic and the southeastern Pacific.

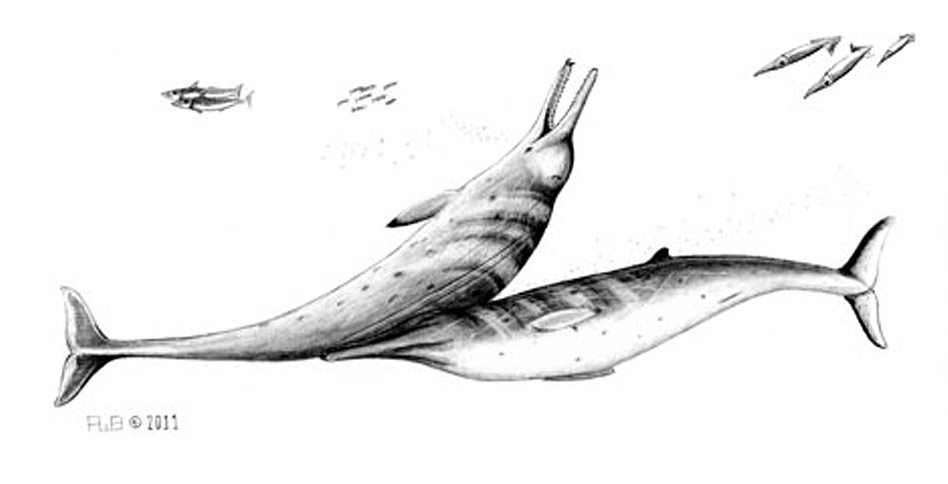

Size: A complete skeleton is currently unknown for Messapicetus, and an accurate size estimate is not possible; however, based on the size of the skull and comparisons with modern beaked whales, Messapicetus may have had a body length of 3-5 meters (10-16 feet).

Anatomy: Although the braincase of Messapicetus is very similar to that of most modern beaked whales, numerous differences can be seen in the snout. The snout is extremely long in Messapicetus, and much longer relative to all modern and most fossil beaked whales. Additionally, Messapicetus retains a full complement of teeth, each with a strangely flattened root. All but one species of modern beaked whales retain a pair (or two pairs) of short tusks on the lower jaw, which may appear at the tip of the lower jaw (as in Ziphius) or in front of the eye socket (as in many species of Mesoplodon). Messapicetus is like the living Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi) which retains a typical set of small teeth, all of the same size, with a pair of small tusks at the tip of the snout. Although currently unknown, the skeleton of Messapicetus was likely similar to that of modern beaked whales.

Locomotion: Although most of the skeleton Messapicetus is not yet known, it is closely related to modern beaked whales, which are fully marine and are among the deepest diving of all mammals (exceeded only by the sperm whales). It is plausible that Messapicetus was a deep diver as well.

Sensory Abilities: The skull of Messapicetus shows many of the hallmark characteristics of modern toothed whales, suggesting that it could echolocate and hear in a similar fashion. In modern toothed whales, a fatty organ called the melon sits atop the skull and acts as a lens to focus sound waves during echolocation. The skull of Messapicetus, like modern toothed whales, has a concave basin on top that houses the melon.

Diet: The diet of modern beaked whales is poorly known, due to the rarity of sightings and difficulty of observing them. However, based largely on stomach contents from beached or harvested beaked whales, they feed on deep-water squid, fish, and even crustaceans from the sea floor. As stated above, only the modern beaked whale Tasmacetus (Shepherd's beaked whale) retains a complete set of teeth alongside a pair of tusks, as in Messapicetus. Unfortunately, Tasmacetus is extremely poorly known; the stomach contents of only a single individual have been reported and it contained mostly fish but one squid beak as well. Other modern beaked whales, which only retain a pair of tusks, feed by sucking soft-bodied squid into their mouths. It is thought that teeth are unnecessary in these species for the capture of soft-bodied prey like squid, and that teeth have been lost over evolutionary time within beaked whales. A similar explanation has also been advanced for the loss of functional upper teeth in sperm whales. The retention of a non-tusk dentition in Messapicetus may indicate that it fed on fish as well as squid.

Behavior: A relatively high number of specimens of Messapicetus gregarius have been reported from a thin section of sedimentary rocks exposed over a small geographic area in Peru. This led scientists to hypothesize that this species of Messapicetus continuously inhabited the area of the sea (now long since gone) that deposited the sediment that entombed their bones. This may be a 'fossil' example of a behavior that biologists call 'site fidelity', or the continued inhabitation (or return) of a particular animal species to a given place or area. Two common reasons that animals exhibit site fidelity are 1) their prey are concentrated in the area or 2) they may congregate there for breeding, as some modern beaked whales do. The large sample of skulls of Messapicetus gregarius is notable in that its shows that Messapicetus gregarius was sexually dimorphic: larger male skulls with tusks and smaller female skulls lacking tusks. This condition is found in some modern beaked whales for which behavior has been inferred: the males of some beaked whales possess long, raking scars that begin to show up at the same time as their tusks erupt, whereas females and juveniles lack scars and erupted tusks. Whale biologists have hypothesized that this pattern of scarring is the result of male-male fighting. The occurrence of sexually dimorphic tusks in Messapicetus suggests that this extinct beaked whale engaged in a similar behavior.

Author: Robert Boessenecker

References Consulted

Bianucci, G., Lambert, O., and K. Post. 2010. High concentration of long-snouted beaked whales (Genus Messapicetus) from the Miocene of Peru. Palaeontology 53:1077-1098.

Bianucci, G., Landini, W., and Varola, A. 1992. Messapicetus longirostris, a new genus and species of Ziphiidae (Cetacea) from the Late Miocene of ‘‘Pietra leccese’’ (Apulia, Italy). Bollettino della Societa` Paleontologica Italiana 31:261–264.

Fuller, A.J., and Godfrey, S.J. 2007. A late Miocene ziphiid (Messapicetus sp.: Odontoceti: Cetacea) from the St. Marys Formation of Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27:535–540.

Lambert, O., Bianucci, G., and K. Post. 2010. Tusk-bearing beaked whales from the

Miocene of Peru: sexual dimorphism in fossil ziphiids? Journal of Mammalogy 91:19–26.

Macleod, C.D., Santos, M.B., Pierce, G.J. 2003. Review of data on diets of beaked whales: evidence of niche separation and geographic segregation. Journal of Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 83:651-665.