News

Race, Medicine, and COVID-19

March 3, 2021

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic individuals are dying from COVID-19 at significantly higher rates than white Americans, with Black and African Americans nearly three times as likely to be hospitalized. Sadly, the pandemic is not exposing a new issue—it’s shining a glaring light on the healthcare disparities that these communities have long faced.

As the medical profession tries to reach these groups in an effort to promote COVID-19 vaccination, addressing these disparities is absolutely critical.

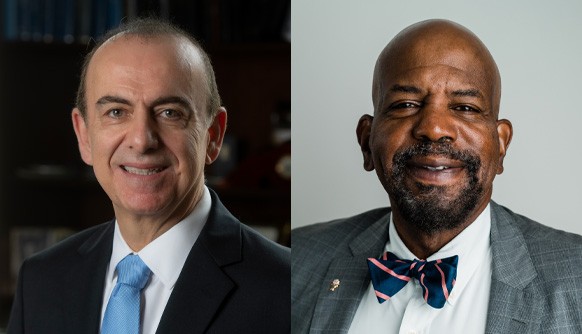

That was the message shared at the February 25 panel discussion, “Race, Medicine, and COVID-19,” featuring New York Tech Chief Medical Officer and Vice President of Equity and Inclusion, Brian Harper, M.D., M.P.H., and panelists Jedan Phillips, M.D., associate dean for minority student affairs at Stony Brook University’s School of Medicine, and NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) alumna Michele Reed (D.O. ’97), founder of Family Medicine Healthcare P.C., which serves Southeast Queens, a community hit especially hard by COVID-19. Throughout the event, the physicians addressed key points for building a more inclusive healthcare environment founded on trusted relationships between physicians and patients.

The discussion began with historical insight on some reasons why the Black community is, understandably, wary of the medical profession, ranging from segregation and bias to medical malfeasance and harmful stereotypes. In the late 1800s, only select hospitals treated and admitted people of color, and many prohibited white nurses from treating Black patients, resulting in poorer health outcomes in communities of color. Harper noted that Black physicians also faced discrimination. The National Medical Association, a professional organization, was established in 1895 for Black physicians to create their own medical societies and hospitals, as the American Medical Association excluded Black physicians for many decades.

Some members of the medical community were not only negligent but predatory. Panelists noted the horrific acts committed by J. Marion Sims, the “father of gynecology.” With no degree in that specialty, Sims purchased enslaved women to perform medical experiments and develop treatments for white women. The agonizing experiments were performed without anesthesia and, in many cases, resulted in death. Another infamous example includes the Tuskegee experiment, where the serious ailments of Black men with syphilis, including blindness, pain, and psychological issues, among others, were purposefully ignored by government researchers for 40 years “in the name of science.”

Harmful rhetoric has further exacerbated issues, most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic. In spring 2020, a deadly rumor circulated that communities of color may have immunity to the virus. The myth implied that these individuals did not require treatment if they suffered virus complications, underscoring that racism and bias in healthcare continue to linger.

Throughout the discussion, Kinsley McNulty, student life program coordinator and event facilitator, asked the experts how systemic racism during the pandemic has affected people of color. Reed said that two pandemics have been taking place over the last year: COVID-19 and racism, referencing the death of George Floyd. She noted that, in some communities, an ambulance would not arrive at homes right away unless someone is “shot and bleeding to death” or in a similar state of dire distress. This reality has led more individuals to seek COVID-19 treatment through her practice, where they know that they will not be turned away or ignored. Philips chimed in, noting that he has even had to pronounce a close familial friend dead in his home at the expense of the disease. These experiences are now driving him to advocate to an even greater extent for communities of color.

Harper also pointed out that, due to healthcare inequality, there is an increased likelihood of pre-existing conditions within these communities, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and stroke. Reed added that today the life expectancy for Black men and women combined is approximately three years less than for white people. These factors all contribute to the higher mortality rates of COVID-19 in communities of color. In comparing COVID-19 to past public health issues, Harper noted parallels to the HIV epidemic, where people of color were more likely to succumb to the disease due to racial stigmas and targeting.

They also spoke about telemedicine and how they used this to treat patients when their offices were closed due to COVID-19, but tech limitations were on display here as well.

The physicians also discussed how COVID-19 disparities, which began with provision of care, now extend to vaccine distribution. Initially, vaccine appointments were available only by computer, limiting access for those who may lack or be unfamiliar with technology, and vaccine locations were also more prevalent in white communities. In addition, Harper noted that vaccine distribution would have been improved by relying on federally qualified health centers, which assist many underserved populations and have an established trust and rapport within communities of color. The group also discussed the overlooked role of Black churches, which would be another valuable driver in vaccinating people of color.

Experts also addressed vaccine fears, including a rumor that vaccines contain chips for human-tracking, contain the disease meant to infect patients, and another that COVID-19 vaccines are ineffective because they were developed quickly. Practicing what they preached, all three physicians noted that they received at least the initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, trusting its ability to keep them safe.

In closing, the physicians shared sage advice for those looking to enter the profession. They called for sincere allies to demonstrate bravery and humility. Allies were urged to “call out colleagues who look like you” in order to overcome the “white coat wall of silence” and educate others on the realities of privilege, social determinants, and other factors leading to healthcare inequalities.